JIM DANFORTH: Matte art's last individualist

It’s with great pleasure that I present today’s NZ Pete Visual Effects 'special edition'.

For decades fanzines, journals and books have dedicated a great deal of effort – and rightfully so – in covering Jim Danforth’s iconic stop motion animation work as well as the convoluted circumstances surrounding the various un-realised features which Jim has tried so hard to get off the ground. Regrettably, no article nor author to date had attempted to cover Jim’s other, quite considerable area of expertise – that being the highly skilled art of movie matte painting which has occupied a significant portion of Jim’s time professionally for around four decades. I suspect that most of Jim’s legions of fans possibly aren’t even aware of the major contributions and vast output that Jim has undertaken in his glass painting effects work. Today’s article will reveal all.

![]()

The following conversations originated as just a few isolated matte shot questions in the first instance and quickly developed into a full blown career interview. It didn’t take long before my overly inquisitive ‘nosey parker’ line of questioning would be fulfilled by Jim’s comprehensive and detailed responses, where no cinematic stone was left unturned.

Jim lovesthe artform, probably even more that I do(!!), and loves to talk about not just his own matte shots but those of industry veterans and even classic effects films that we share a common respect for. Jim’s enthusiasm was such that he “wrote off” at least one computer keyboard in the process of typing up material for me! Now that’s dedication.

![]()

I want to thank Jim most sincerely for donating so much of his time to furnish this author with so many answers to matte matters I’ve always been curious about as well as many great anecdotes surrounding the personalities and politics of the movie business. Not only was Jim generous with his time and knowledge, but also with diving into his substantial archive of 35mm frame enlargements and behind the scenes photographs, the great majority of which appear here for the first time anywhere.

A word too of thanks to Jim’s wife Karen, who not only assisted Jim on many effects shots over the years, but tolerated his spending so much time on line to a certain blogger in the South Pacific while his dinners got cold. Thanks are also due to David Stipes and Harry Walton for additional photographs and stories of "the good old days".

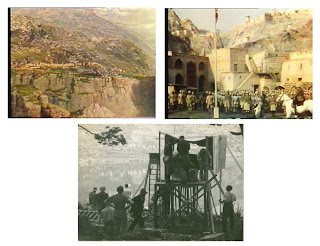

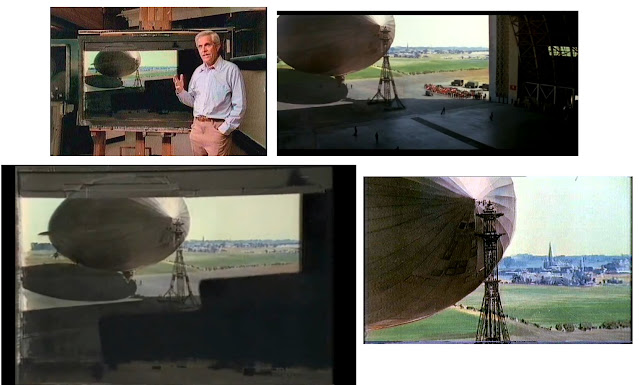

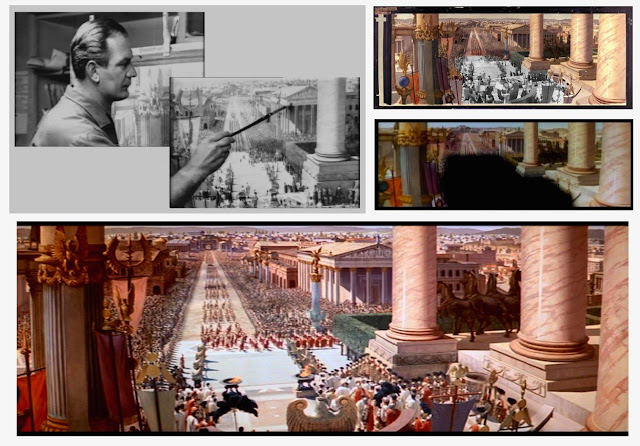

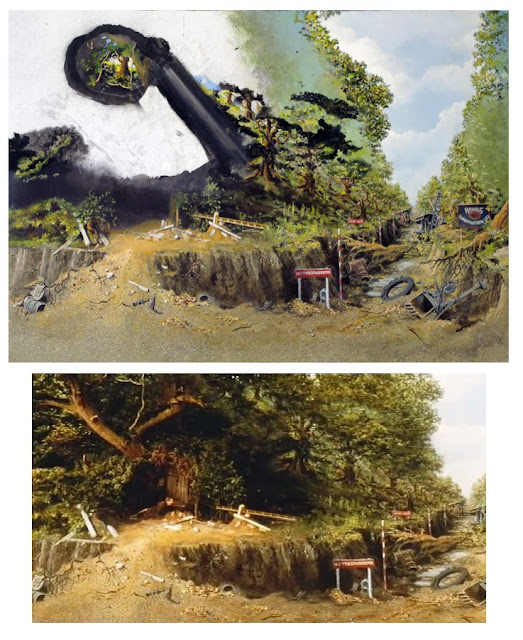

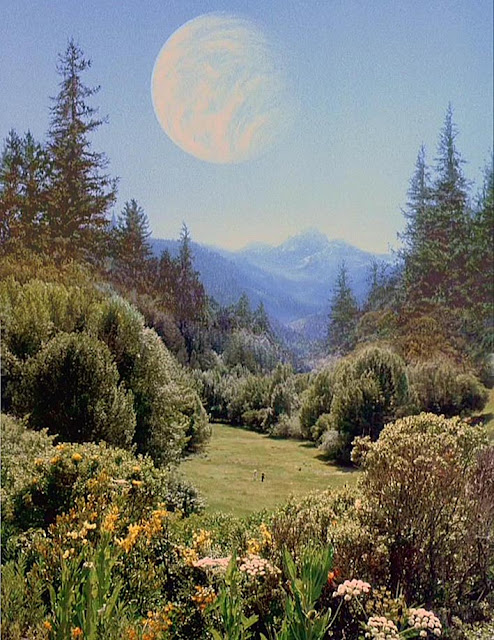

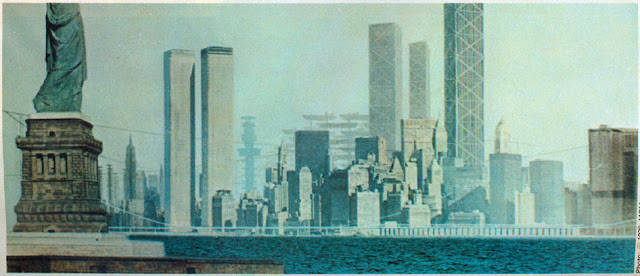

![]() |

| Jim Danforth and Karen Tuttle (before she became Mrs. Danforth) working on THE BLUE AND THE GRAY at their company, Effects Associates, Inc.. This shows Jim's very simple matte stand and his electro-mechanic controller that synchronized the camera and up to two projectors. Karen is holding the miniature flag that was photographed in front of a real sky, with smoke blowing past it. That image was projected behind the upper part of the painting, with the image of an Arkansas street and actors projected below. The various elements are shown later in this article. |

![]()

Q: Firstly let me say what a pleasure it is to interview you Jim. I’m most grateful for your time and willingness to share your cinematic experiences.

It goes without saying that I’ve been a huge fan for many years, with probably old, well thumbed through issues of Forry Ackerman’s Famous Monsters of Filmland being the initial exposure to your work as best I can recall, as it was for presumably tens of thousands of like minded film buffs. Just before I launch into a multitude of matte and effects questions perhaps you’d like to comment on Forry and his huge influence on legions of not only genre fans, but fully blown effects people such as yourself and many others like Phil Tippett, David Allen and Dennis Muren?

JD: Forry Ackerman was very influential for me and many others. He was, for a long time, the only readily-available source of information about genre films and those who made them.

![]()

Q: There really wasn’t any other source for us sci-fi and monster hungry youngsters to find info and behind the scenes pictures on visual and make up effects – even less so far away in the South Pacific isolation of New Zealand, I can tell you! It has always been with great regret that I never visited

The Acker-Mansion when I had the chance on numerous visits to California. Of course it’s all gone now – dispersed to the four winds.

JD: Yes, the Ackermansion was… well, unique. Forry’s collection began to be dispersed even while Forry was alive—sometimes without his knowledge. I’d like to know where some of his original Willis O’Brien art work is now (and a couple of my contributions, too).

![]() |

| Visiting the Ackermansion |

Q:

Yeah… I’ve heard of occasions where irreplaceable movie memorabilia would vanish up under the sweaters of overly enthusiastic visitors! Man, do I

still love those FM covers!

Tell us Jim, what sparked ‘the film bug’ in you, and what was that first breakthrough movie which ‘lit the trick photography fuse’ as it were?

JD: The fuse had been smoldering for a while with home-movie and stop-motion experiments begun when I was twelve, but the explosion occurred when I saw a reissue of KING KONG.

Q: It really couldn’t have been any other. A great many effects technicians, including very prominent figures such as Ray Harryhausen found their inspiration (to put it lightly) in the Cooper/Schoedsack masterpiece KING KONG, while many of the next generation of effects people were seduced by Ray’s own films, most notably THE 7th VOYAGE OF SINBAD and JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS, which both seem to figure prominently in so many effects bios of guys like Bill Taylor, Richard Edlund and Dennis Muren.

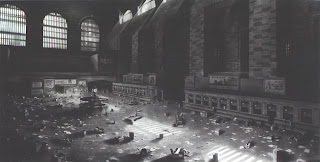

![]() |

| A very early glass painting Jim made for his proposed version of 20'000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA. The glass here is positioned so that a real sky and clouds show through. |

JD: Yes, which stop-motion film was most influential seems to be dependent on the age of the respondent at the time the influence was first exerted. For me it was KING KONG, but THE 7

TH VOYAGE OF SINBAD also had a big impact on me. I was already working in the film business when I saw 7

TH VOYAGE.

Q: Pioneers such as John Fulton, Willis O’Brien, David Horsely, Percy Day, Fred Sersen, Emilio Ruiz del Rio and Jack Cosgrove have entranced this author since I don’t know when. Any personal views on these, or any other ‘old style’ effects men Jim?

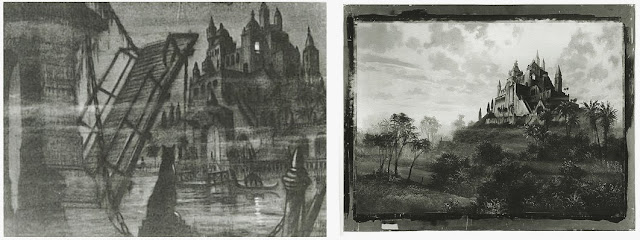

![]() |

| Early Danforth multiplane matte art . |

JD: When I was younger, the work of the Lydecker brothers made a big impression… in addition to that of Willis O’Brien, Mario Larrinaga, Ned Mann, and Peter Ellenshaw. David “Stan” Horsely was the cinematographer on JACK THE GIANT KILLER, a film on which I worked, but I didn’t have any direct contact with Mr. Horsely.

Q: Yes, Howard and Theodore Lydecker were in a class of their own. If I may, could I ask you your thoughts on successful trick shot design. What makesa good shot work? How do you ‘think’ out a prospective visual effect?

JD: Since my primary interest has always been on making films with an emphasis on visual effects rather than effects just for themselves, I usually think first about the arrangement of a sequence—particularly in the case of stop-motion animation sequences—how the shots will be edited, what the tempo is, and so on. But even with matte shots, I tried to interject some of my own philosophy about sequence design—tried but rarely succeeded. It seems to me that having only one spectacular matte shot in a sequence calls attention to itself in an undesirable way and could result in what Al Whitlock referred to as “the JOHNNY TREMAIN problem”—small live-action sets combined with spectacular painted vistas. My view was that it would be better to include one or two matte shots that weren’t spectacular—just enough painting to suggest that, the sets or locations were larger than they actually were. In that way the ‘big’ vista would be less jarring.

![]() |

| A practice matte Jim did in 1959 just for his own education—no attempt to composite it. |

Q: I’ve had many industry people remark very positively about your VFX ‘shot design’ ethic.

JD: I have heard a few of those comments—usually from other effects people rather than from producers or directors.

Q: If I put a few effects film titles to you, I would be interested to hear your professional visual effects evaluation in a capsule: THE INVISIBLE MAN…. IN OLD CHICAGO…. KING KONG…. GONE WITH THE WIND…. THIRTY SECONDS OVER TOKYO…. THE THIEF OF BAGHDAD…. QUO VADIS…. DARBY O’GILL AND THE LITTLE PEOPLE…. THE BLACK SCORPION…. 20’000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA …. GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD…. COLOSSUS – THE FORBIN PROJECT….. BLADERUNNER.

JD: Please keep in mind that my judgements tend to be harsh.

THE INVISIBLE MAN: Crude but effective—crude when compared to the very subtle effects in DEATH TAKES A HOLIDAY, made at about the same time.

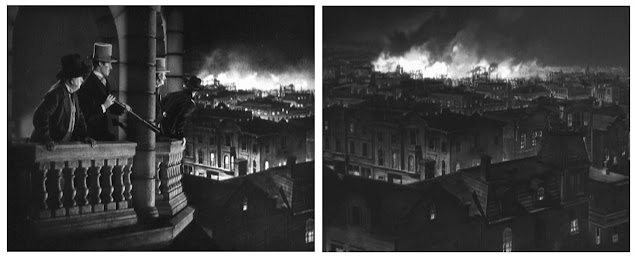

IN OLD CHICAGO: one of the very best ‘disaster’ films—along with THE RAINS CAME.. Beautifully integrated effects.

KING KONG: Ground-breaking despite some obvious effects flaws. A triumph of shot design over some technical limitations. Later refinements did not result in similar films with as much impact and artistry as KONG.

THIRTY SECONDS OVER TOKYO: Very well done, all around.

GWTW: Highly variable matte paintings, that result in an overwhelmingly wonderful cumulative effect—one of my favorite films. Nice design work by William Cameron Menzies.

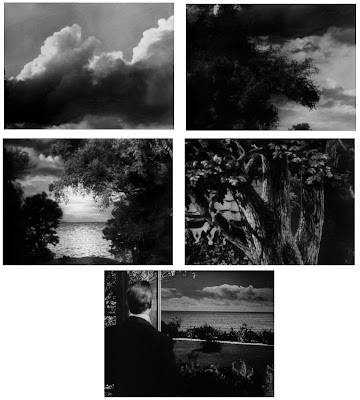

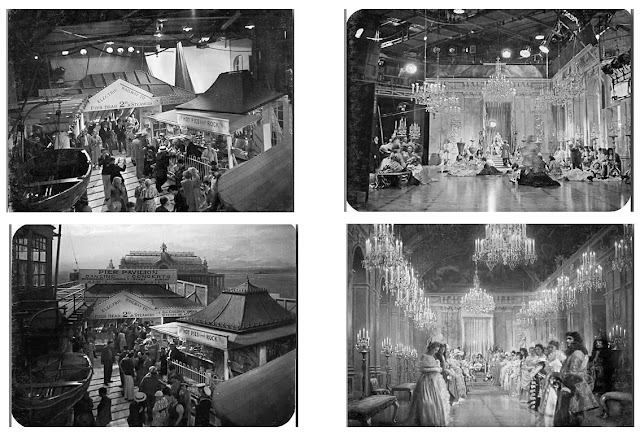

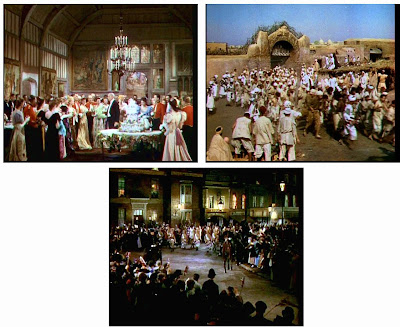

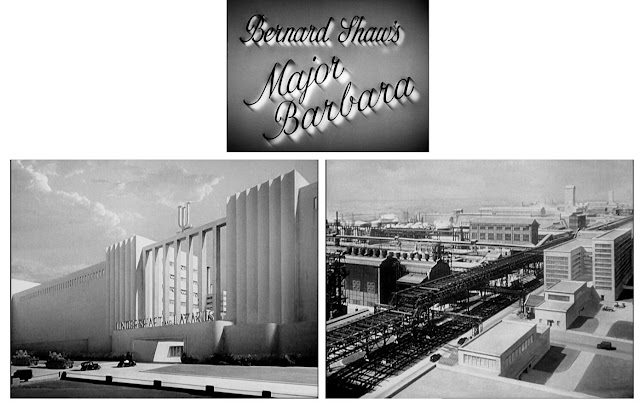

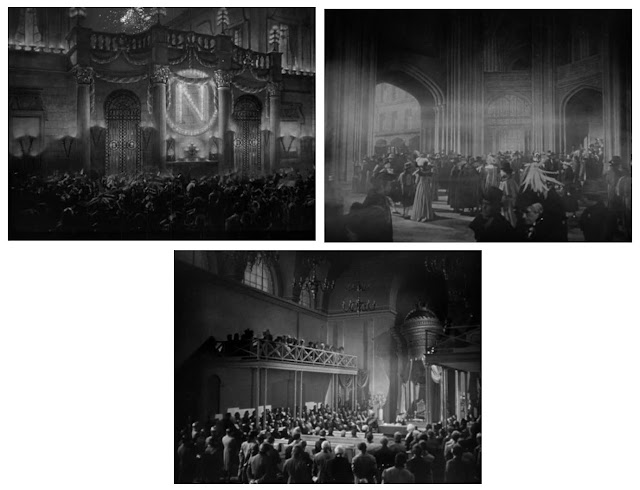

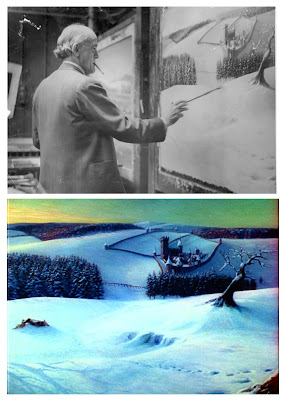

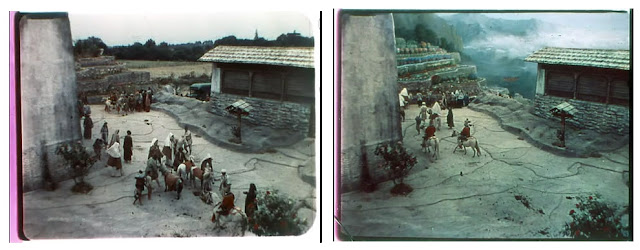

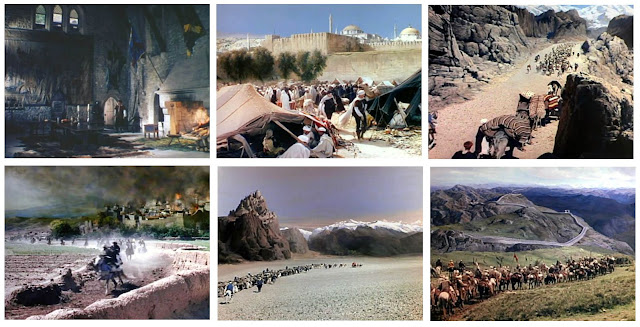

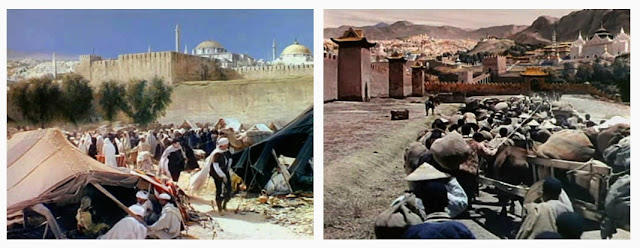

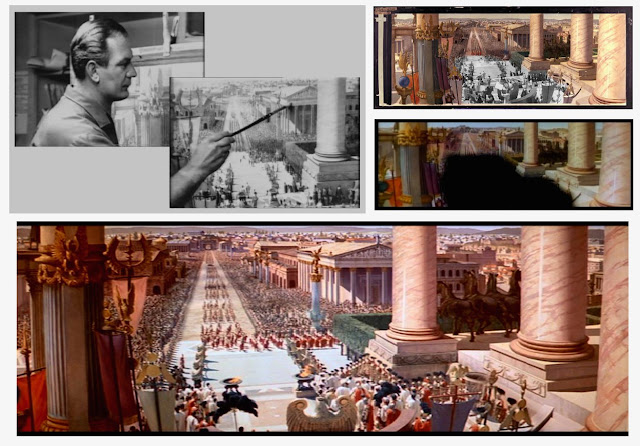

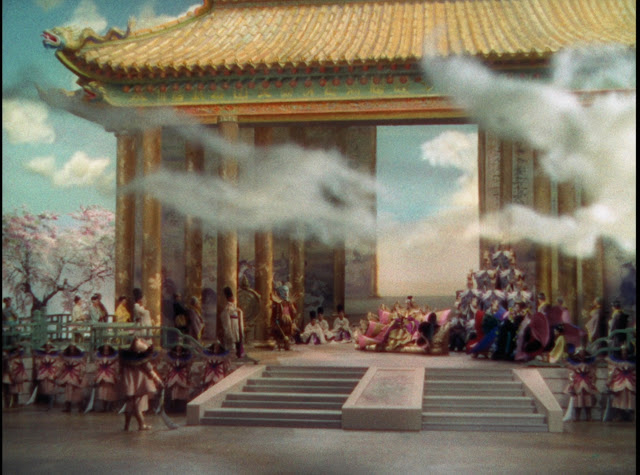

THE THIEF OF BAGDAD: Poetic, with utterly superb matte paintings and hanging miniature shots, plus the first-ever three-color traveling matte work (which permitted the story to be told, despite some technical flaws.)

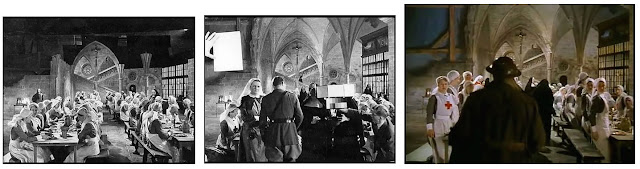

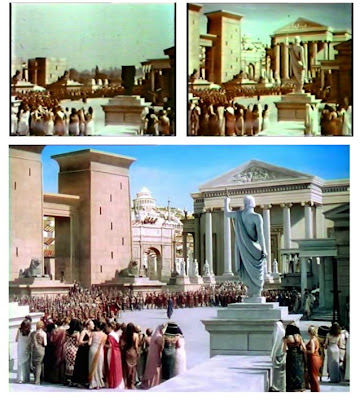

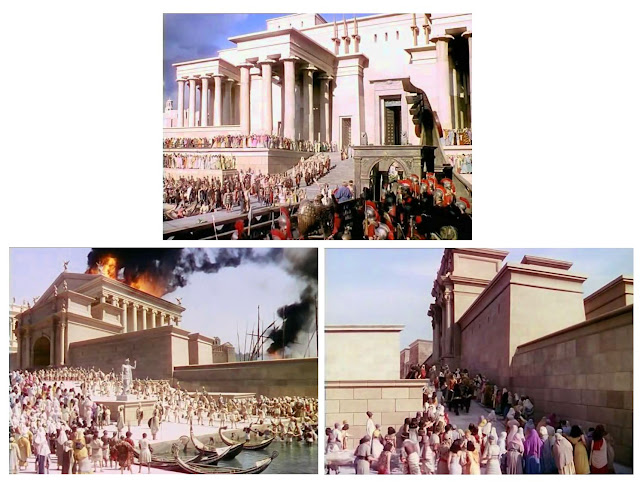

QUO VADIS: Spectacular, in all departments—superior matte paintings and traveling mattes.

DARBY O’GILL: The best mixed-scale effects I’ve seen, plus beautiful matte paintings and real solarization effects.

20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA: In my opinion, the best-designed miniature ship scenes ever. Great integration of painted tank backings and glass and matte art. The Nautilus lying in wait for the nitrate ship at sunset is unforgettable. But what else would one expect with Peter Ellenshaw and Ralph Hammeras collaborating—plus Harper Goff’s design of the Nautilus.

THE BLACK SCORPION: A great example of how to create mood with a restricted effects budget. If only the ants in THEM had been as exciting as those scorpions.

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS: highly variable effects, with some lacking in subtlety—the burning bush being an exception. The excellent designs may have been beyond the capabilities of the time, although I think if Gordon Jennings had done the effects (as was planned), I would have liked the results better.

THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD: Disappointing, although the choreography of Kali is very well done.

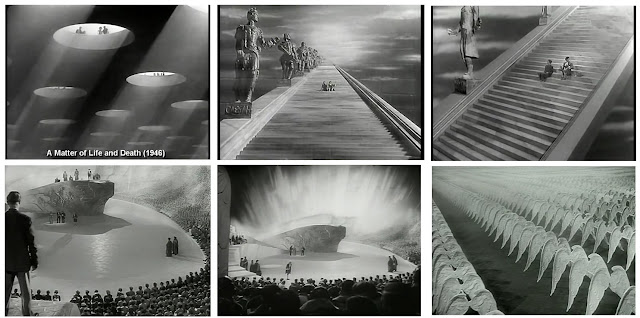

COLOSSUS-THE FORBIN PROJECT: A very intelligent film. Whitlock’s daring original-negative computer start-up shot is famous in the world of matte paintings.

BLADERUNNER: Not a film I liked, although the matte work is excellently done.

I think the art direction and the paintings totally achieved the desired effect. It’s just not an effect I happen to like.

Peter Jackson’s KING KONG: I can think of nothing good to say about that film, except that I liked the introductory shots of New York.

Q: Well, that was interesting. Most of those I’d have similar thoughts, though I loved GOLDEN VOYAGE myself – a light year ahead of the very poor final Sinbad picture EYE OF THE TIGER, which followed it. I actually really liked the latest KONG and thought Andy Serkis made an amazing and unique contribution to this and the recent Planet of the Apes picture.

![]()

There are many articles and interviews over the years with you Jim where the key area of interest has centered on your stop motion animation projects, yet very

fewjournals (if any) have covered your quite substantial matte painting career. I’d like to kick this off with the question I’d like to present to

all matte painters: if you’re able to recall, which was

theglass painted shot which made that impact and triggered off that ‘love’ of the artform for you? (film/shot?)

JD: First, I think I should point out that my animation work got more attention than my matte work because animation is part of the story, which is what most people are interested in. Secondly, animation calls attention to itself because it is inherently ‘phoney’ of theatrical. A well-done matte painting recedes into the background, although mattes can be very memorable and evocative.

![]() |

| Monoclonius drawing is from Jim's production TIMEGATE. The film was not finished. Drawn in graphite and reproduced as a brown-line print for presentation. |

But, to answer your question, I suppose it would be KING KONG and the arrival at Skull Island shot. The setting is almost a character in that film and was created largely by glass art. Of course, when I first saw it, I had no idea how it was done.

Q: Oh yeah, that shot is iconic, though I thought the similar establishing glass shot in SON OF KONG to be even better both in terms of composition and a far cleaner composite. I just loved the Orville Goldner animated birds doubled into the former shot.

I absolutely adore the matte painted effects shots from The Golden Era, with probably late twenties through to late forties encompassing the artform at it’s most essential and‘magical’… the proverbial Dream Factory. The use of the matte process was at it’s peak, with vast visual effects departments and large numbers of artists turning out hundreds of mattes per year. Would you have liked to been a part of that era Jim where the painted matte was so extensively used and highly valued?

JD: No.

![]() |

| A full frame matte that Jim painted for a television commercial where an actress would magically slide down the bannister via travelling mattes. Jim expressed a degree of dissatisfaction at his perspective work here, though I can't see a problem. |

Q: You are generally acknowledged as one of the effects industry’s most ‘individualistic’ visual effects creators from my understanding, so would you feel comfortable as part of a large stable of matte painters, such as the Warren Newcombe unit at MGM or Ray Kellogg’s team over at Fox for example?

JD: No.

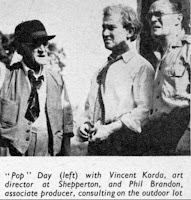

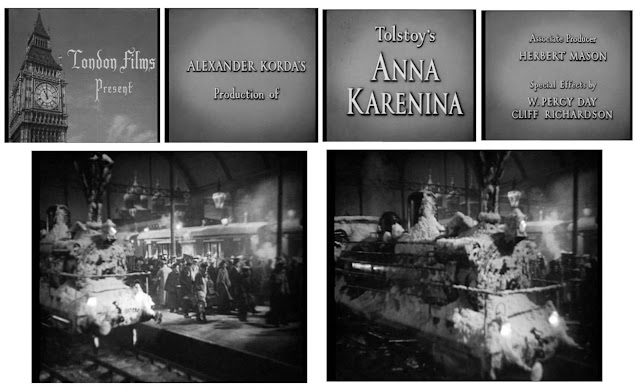

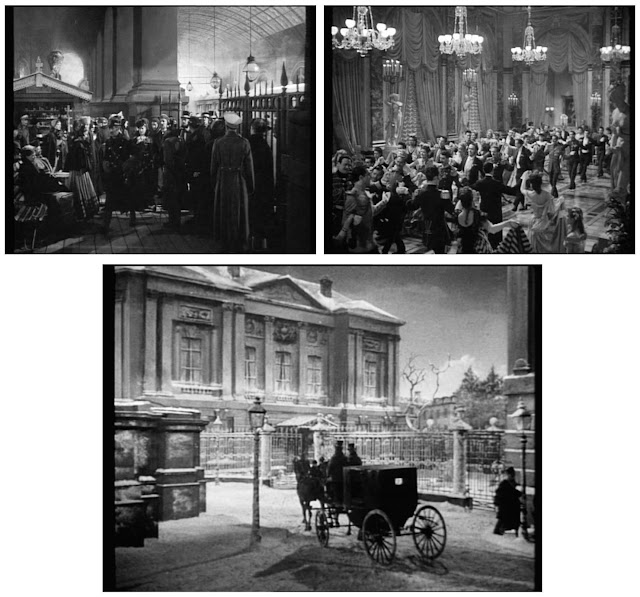

Q: From my research, Walter Percy Day, England’s most eminent matte painter based at Denham Studios, would control each and every step of the process for his stable of painters where they were required to paint only as expressly directed by the master with no room for individuality. It was almost a ‘paint by Pop’snumbers or not at all’ scenario it seems.

JD: I suppose the idea was to get the Walter Percy Day look that the customer was paying for, and only Pop Day knew how to get it—or thought so.

Q: There’s no disputing Poppa Day was the master in my book, with a phenomenal catalogue of glass shots over a very long period, with much of his best work in the silent French cinema. I lost count of how many ornate ceilings and ballrooms Day must have painted.

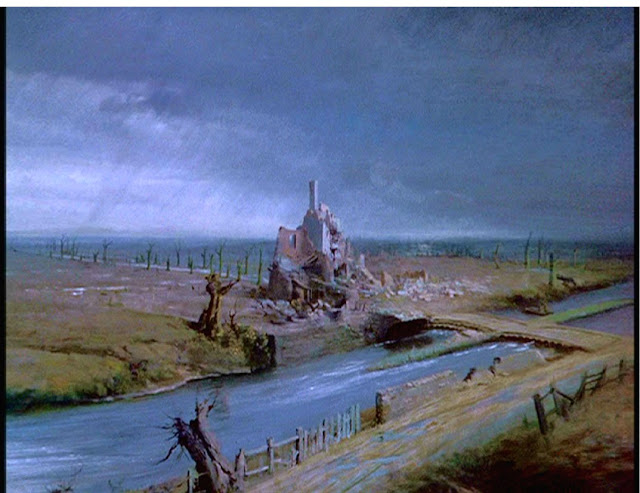

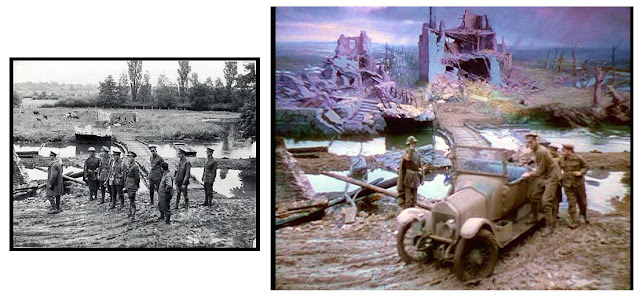

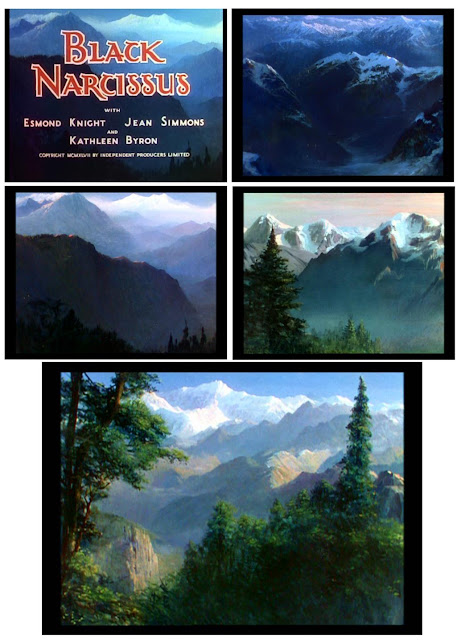

JD: I wish I knew more about Day’s entire career. I really, really like the work he did for Korda and on BLACK NARCISSUS, but some of his later work, such as THE BLACK ROSE is, in my opinion, not very good.

![]() |

| Jim at work on a foreground painted matte on hardboard for EQUINOX. Jim says he wasn't too happy with this painting, but again, it looks great to me and I'd happily own it. |

Q: I’m interested in your thoughts regarding the various Golden Era matte departments’ styles and technical methods?

JD: I think there was a certain amount of “not invented here” in effect during those years—meaning that methods used effectively at one studio might be shunned by another. In part that was due to the type of equipment in which a studio had invested. In part it was due to the preferences of whoever was in charge of the matte department at a particular studio (which, of course, influenced the equipment that was constructed).

Clarence Slifer at MGM refused to believe that Al Whitlock did most of his mattes on the original negative, so Matt Yuricich phoned Al and put Clarence on the phone. Al explained to Clarence how he did his shots. After the conversation ended, Clarence turned to Matt and said “Well, maybe he does and maybe he doesn’t.” What was an everyday procedure for Whitlock was inconceivable for Slifer, even though Slifer had used the same procedures in earlier times. Sometimes one can ‘brainwash’ oneself.

My understanding is that Jack Warner liked clouds in the matte shots of his fims, so that was an influence from outside the matte department. Also, I was told that at Warner's it was common to use matte paintings to improve the apparent focus on the foregrounds of miniature sets. When shots of miniature trains had out-of-focus foregrounds, the foregrounds were matted out and replaced with sharp, painted versions of the miniature.

The quality of mattes sometimes changed within a studio as the department head changed. I thought the mattes done at MGM during the period when Lee Le Blanc was in charge were not as ‘artful’ as those done by the Newcombe department.

![]()

At Fox (and at Film Effects of Hollywood), precision-machined aluminum grommets were pressed into holes drilled in the hardboard panels on which the mattes were painted. The holes in the grommets fit over pegs on the photographic easels. At Universal, Al Whitlock simply slid his paintings into a channel on the matte stand and pushed them until the wood frames encountered a ‘stop’ on the matte-stand frame. When Al did dupe composites, he used the un-illuminated opaque painting on glass as a hold-out matte when duping the live action from separations while photographing a brightly-lit white background positioned behind the painting. Then the painting was illuminated and photographed over a black background to double expose it onto the film with the live-action dupe. The painting and the ‘matte’ fit perfectly. At Fox, registration pegs were necessary because the board with the painting was not the same board used to dupe the live action. A duping board was created by placing the board with the painting on a tracing table with identical registration pegs, then lowering an aluminum frame, to which had been taped a large sheet of translucent plastic tracing ‘vellum’, then tracing the matte line from the painting board onto the vellum. The painting board was then removed. A new board, painted pure white and fitted with the same type of grommets, was the placed in registration on the tracing table, and the matte line position was transferred onto the duping board. The duping board was then painted gloss black in the area corresponding to the area to be occupied by the painting. The painting board was painted gloss black in the area to be occupied by the live action. The visibility of the matte line was dependent on the accuracy of the tracing, transfer, and blacking in. Which system do you think was faster, the Universal system or the Fox?

RKO may have had the most versatile matte department, in the sense that they used different methods for the composites, depending on the requirements. Linn Dunn told me that at RKO they had one artist who specialized in doing the blends for all the paintings. As I recall, that artist was Paul Detlefsen (who later painted fine-art illustrations in a neo-Currier & Ives style).

Many of the mattes at RKO were put together using the same rear projection process patented by Willis O’Brien in 1928 (granted 1932).

Disney utilized the ‘O’ Brien’ projection method for most of the matte shots done at the Burbank studio by Peter Ellenshaw (with equipment modified and/or engineered by Ub Iwerks) up until they switched to projecting separations (around the time that Alan Maley took charge of the department, I think) But that was well past the ‘Golden Age’.

![]() |

| "Dreams of Power" is a wonderful piece of concept art for JONGOR—a 'pulp' jungle adventure property Jim optioned from the author's estate in about 1983. The 'maguffin' is Lemurian levitating crystals. |

Q: Some studios seemed to hold the high ground, with Metro Goldwyn Mayer’s enormous resourses no doubt a prime factor in the quality of the output from Newcombe’s matte department. Fox and Warners both had huge effects staff, with the latter employing some eight painters at their peak. Universal on the other hand, by all accounts had a tiny matte department as far as I know, with just the one painter, Russell Lawson, for several decades. Some of there large matte shows must have surely seen additional painters brought on board to turn out the number of mattes required, and I’m thinking here of Hitchcock’s wonderful and exciting SABOTEUR – a huge matte shot show. I heard somewhere that well known Art Director John DeCuir may have painted mattes on that film with Lawsen?

JD: I really don’t know anything about the mattes on SABOTEUR. I thought they were variable in quality. I remember the Statue of Liberty mattes as being very good.

Q: There were an awful lot of mattes in that show, some really invisible such as the stuff with the ship at the docks as well as several ceilings. Could you tell us a little about your own earliest experiments in glass painting Jim?

![]() |

| An early glass painting by Jim for a non-professional version of 20'000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA. Even at a young age the skill is readily apparent, as is the drive. |

JD: When I was about fourteen or fifteen, I started painting ‘tests’ for my own amusement and education. Originally, I used water-soluable tempera paint (poster paint), because I didn’t know any better. After the paint dried, it tended to flake off the glass. I did some glass paintings for an amateur version of 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA that my friends and I worked on for many months but abandoned before any ‘principal’ photography was done. Then I did a painting on bristol board to be used as an establishing shot for a 16mm version of THE PIT AND THE PENDULUM (this was several years before Roger Corman made his film). I based the layout on the famous painting “Toledo in a Storm” by El Greco. Holes were cut in the bristol board so I could backlight the windows of the buildings. (This was before Al Whitlock taught me that was unnecessary—that if one painted in the correct key, painted lights would photograph bright enough.) I abandoned PIT for a more interesting idea: GERALDINE IN JEOPARDY—a humorous 16mm silent serial set in the time of the American Civil War. For that project, I painted a house on glass and also tents and a canon and a watch tower for a scene of General Grant’s camp. The house shot was filmed in a local park, with ‘Geraldine’ running toward the non-existent house, but the glass of General Grant’s camp fell over and broke while we were setting up on location.

Then I did a “Hall” hardboard shot of a jungle setting which I photographed in 35mm with me moving cautiously toward the jungle area. This was for a test involving a phororhacos.

![]() |

| Jim and Karen and part of the crew at Snowbird, Utah, filming the plate for a matte shot for John Carpenter's MEMOIRS OF AN INVISIBLE MAN. Ted Rae was the cameraman. That's his camera. |

In between these projects, I experimented with projecting small areas of live-action into glass paintings, in the manner of KING KONG. My results were not good.

Q: Was there ever a time where you saw yourself as becoming purely a studio matte artist or were your cinematic interests far too varied to allow you to settle into just one creative slot?

JD: I didn’t want to do visual effects; I wanted to make films (with visual effects). Visual effects—particularly stop-motion effects—seemed to be the entry-level job most related to general filmmaking.

Q: I’m very interested in your early ‘cold call’ encounter with Disney matte department head Peter Ellenshaw? That must have beenone unforgettable experience?

JD: Absolutely right. I’ve described that experience in my memoir. The three things that impressed me the most were: A) the realistic effectof Peter Ellenshaw’s paintings compared to their very loose style on close examination. B) Ellenshaw the man—very gracious and charismatic. C) The clarity of the rear-projected 8-perf. (VistaVision) images used in Ellenshaw’s department for compositing most of the mattes.

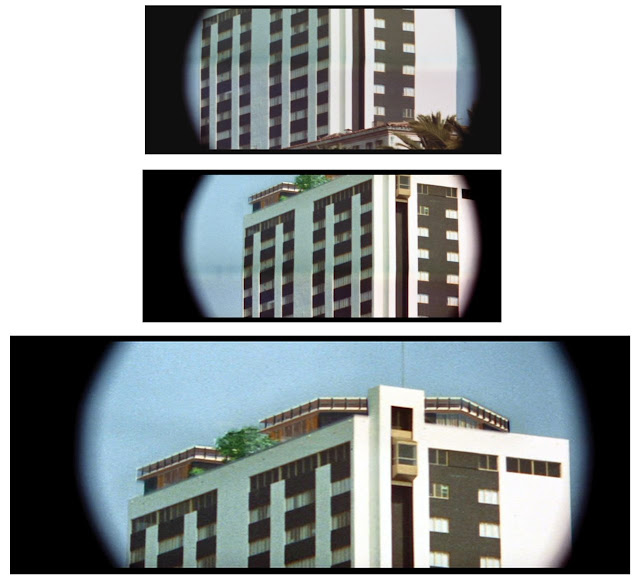

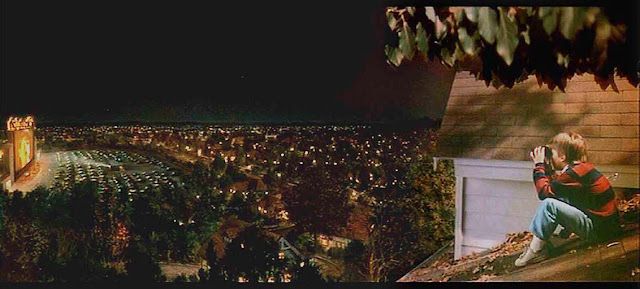

![]() |

Not all mattes are spectacular. This is from JOHN CARPENTER'S THEY LIVE. Jim added fictitious advertising paintings to several existing buildings. The challenge in this shot was to get the effect of old, weathered paint that was slightly faded and absorbed by the concrete. For the background of this Panavision film, Jim used dual-interlaced rear projection, which yielded more detail than a VistaVision frame would have for a 'scope extraction. The advertising signs were camouflaged subliminal messages. Those messages were also matte paintings that wiped on or were intercut when the protagonist used his alien dark glasses. |

Q: How many painters and cameramen did Ellenshaw have with him at that time?

JD: In addition to Ellenshaw, the only other artist I saw was Al Whitlock, although I understand from your blogs that Jim Fetherolf may also have been at Disney during that time. Peter also introduced me to an assistant who worked in the room where the paintings were photographed. I don’t remember his name. Ellenshaw mentioned that the man had worked on KING KONG.

Q: Was there ever the possibility of you taking up a matte painting position in Peter’s department? Would you have done so had the invitation been forthcoming?

JD: It was never mentioned, and I never thought about it. Remember I was VERY inept at that time. I was nineteen. I suppose that if the opportunity had presented itself a few years later I would have jumped at the chance.

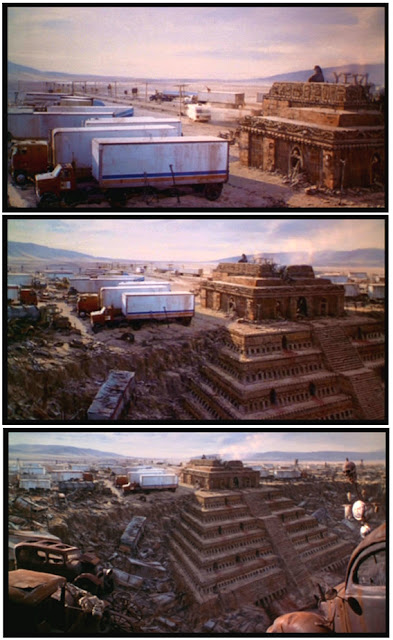

![]() |

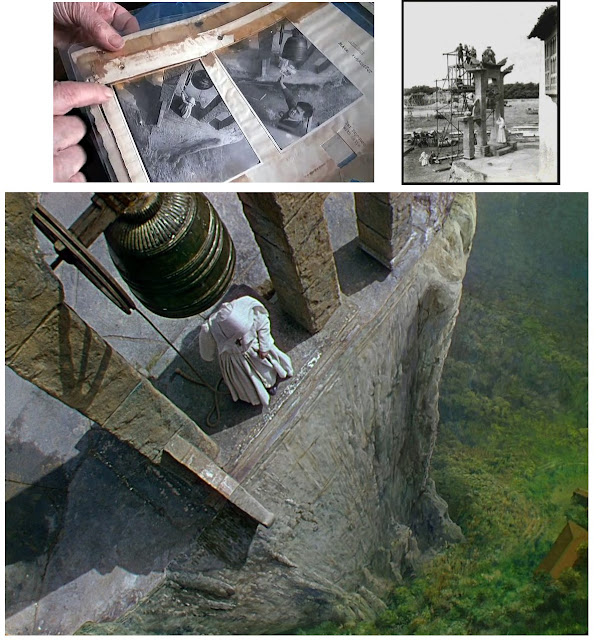

When is a matte shot a backing and vice versa? Jim with a backing he painted for TIMEGATE— an uncompleted feature. The backing didn't need to be detailed, because it got matted into the live scene at a reduced size—an example of the "big brush" approach. The live-action scene with the area to be occupied by the backing matted out (from a faded daily print). Test composite showing that backing ties into live action quite well. The softness of the blend can be seen at the left, where the foreground cliff edge will later be sharped by a small strip of glass painting.

The backing was used so that miniature dust could be shown drifting out of the canyon, following a rock avalanche. |

Q: Peter’s son Harrison told me recently of an occasion in 1964 in which he temporarily worked as an intern in his father’s department and he got to know artist Jim Fetherolf. Jim was, according to Harrison, an excellent artist, but sometimes very frustrated working at Disney. Fetherolf would say: “I don’t know why I even bother to do this, as Peter will just walk in later and change it all with a big brush and make it better”. As I understand the situation, Albert Whitlock had similar issues and wanted to break free.

![]() |

| Peter Ellenshaw |

JD: Al never mentioned to me anything about Peter reworking Al’s paintings. Al disagreed with some of Peter’s methods when it came to

effects techniques, such as the pin-hole glasses used to add highlights to painted water. Al was bothered by the fact that the sparkles reappeared in exactly the same place every time. Al’s idea was to slide both the pinhole glass and the interrupter glass, so that the sparkles would seem more random. Al had to wait until he got to Universal to implement ideas like that.

Q: Harrison also mentioned to me that although various artists painted the shots on Disney pictures, there were probably few instances where the painting left the easel withoutPeter having dabbled away upon it with his brush or changed things. How would this sit with the average artist I wonder?

JD: Well with a fine-art painter, not well, but matte painting was more of a craft than an art, in some ways, so many junior artists probably accepted it.

Q: Would I be correct in suggesting that the Disney effects operation was very much a tightly run factory with a regimented and conservative structure with the accent on ‘pure painting’ and nothing more for the artists?

![]() |

| Albert Whitlock |

JD: I’m not sure about that. I know that Al Whitlock made a lot of decisions on KIDNAPPED. I also remember him telling me that he had convinced Peter to rework one of the paintings Peter had done for THIRD MAN ON THE MOUNTAIN, because the rock face was too ‘geometric’. Apparently another Disney person had said something similar to Peter about the same painting. Peter said

“Since I’ve heard this comment from two people, I’ll rework the painting”. Al told me that during MARY POPPINS, Peter was having a problem with a green shift on the color of the projection of Mary sitting on the cloud . Peter asked Al whether Al could see any green in the projection (he couldn’t). When Al was painting mattes for the black and white TV show ZORRO, he disliked the shade of gray that resulted from mixing black and white paint. Al started painting in

green and white. And, of course, Al did several Disney assignments on his own, such as TEN WHO DARED. I’d say there was a certain amount of give and take going on in the Ellenshaw department.

Q: I’ve heard that some Disney artists were also frustrated at the embargo imposed on trying new gags and styles, such as Alan Maley wanting to experiment with Front Projection for compositing and Al Whitlock wanting to develop his split screen moving sky animation, which of course he mastered once he moved over to Universal.

JD: I don’t know about Alan Maley’s frustration. Possibly the reluctance to change was due to the investment in time and money that had been put into developing the VistaVision rear-projection and masking system, which I understand was perfected by Ub Iwerks. Personally, I’d choose rear projection over front projection for a matte painting situation.

Q: Were Disney still using oils to paint or was all of the matte work being painted with acrylics by this time?

JD: In 1959, when I visited Ellenshaw, the paintings were done in oils. As I recall, acrylic paints for artists didn’t make an appearance until several years later.

![]() |

| Jim Danforth and Tom Corlett painting a convention hall full of refrigerators for a projection pull-back shot as part of a Cascade TV commercial |

Q: You have had a long association with Gene Warren, Wah Chang and Tim Baar and their effects house Project Unlimited. At a time where effects units were primarily big studio based departments with a considerable chain of command and power politics, was an independent operation like Project Unlimited seen as an oasis of creative freedom in what was then a very ‘front office and mogul’ run industry?

JD: I suppose so, but then I’d had no experience at that time with the “mogul-run” industry. Later, Project Unlimited did seem to have more freedom, particularly since the restrictive union policies of the major studios were not rigorously applied, even though Project was a union signatory shop and we all belonged to the IATSE.

Q: Could you tell us about your role at Project Unlimited. I understand you were involved with assisting Gene Warren on some of the special effects shots for one of my favourite films THE TIME MACHINE?

JD: I didn’t assist Gene, except in the sense that all the employees assisted him to get the jobs completed. Gene only rarely did any hands-on work by the time I started at Project Unlimited. I did assist Bill Brace with some lighting manipulations during the TIME MACHINE, but I didn’t do any painting (except for a black matte with which I assisted Wah Chang).

Q: Would you like to describe the facilities and equipment at PU? Were they set up for all aspects of optical cinematography for example or were such shots farmed out elsewhere?

JD: Project Unlimited could do NO optical effects when I started. They were primarily a prop-making shop and stop-motion facility. At first, all the optical work was farmed out to optical companies or sent back to the optical department of the studio making the film.

![]() |

| A Bill Brace matte from THE TIME MACHINE. |

Q: As much as I really enjoyed (and still do) THE TIME MACHINE I have always had issues with many of the visual effects shots. Many of the Bill Brace painted mattes are iconic classics, such as the Eloi Temple –

but the composite photography of most of the matte paintings is

not of a high standard, with huge black ‘magic marker’ matte lines. What went wrong there? It was unusual to see such hard edged mattes (see right).

JD: What went wrong was Project not having any compositing facilities, nor a thorough understanding of how to approach compositing. That may sound like a judgemental view from a nineteen-year-old, but I had spent hours in the AMPAS library and other libraries, making a careful study of effects techniques.

Bill’s paintings that were intended to be composited with live action were painted on black and white photo enlargements. They were photographed just as they looked, with the black and white photo visible. The film of the painting was delivered to The Howard Anderson Company where a film matte was created to block out the live-action area. A negative print of this matte was use to block out the area of the live action into which the painting would be inserted. There was no way for Bill to blend his painting to the live-action photography. All join lines had to be hard-edged. Because of the nature of the shots, I don’t think it was necessary for Bill to make any composite tests. All the color balancing and matte fitting was done on the optical printer.

![]() |

| TIME MACHINE split screen. |

The worst of the “black-line” matte joins was one that was not really a matte painting but was a combination of two locations. Perhaps Luis McManus had done a little work on that shot; I don’t remember. The composite work for THE TIME MACHINE was supervised by Phil Kellison of the Anderson company.

Q: What method did PU favour for their matte composite photography?

JD: Having someone else do it…until I convinced them otherwise for THAT FUNNY FEELING.

![]() |

| The destruction of London from THE TIME MACHINE |

Q: The depth of field issues in the lava flow disaster sequence in London were pretty unacceptable too. From what I’ve seen the miniatures were reasonably large, yet for some reason the combination of artificial light and totally inappropriate focal length lenses were not the best decision.

JD: I agree. Those scenes were finished before I arrived, but then they wouldn’t have listened to me anyway.

Q: The Academy oddly didn’t seem to mind – though I’ve had so many problems with strange AMPAS decisions over the years I suppose it doesn’t surprise me. It’s still a great little film though.

JD: It’s a film that didn’t capture the feeling or mood of the Well’s novella, but it became a nice film on it’s own, as did 7 FACES OF DR LAO.

Q: I understand that Bill Brace did most of the matte painting for PU, with former Roy Seawright matte artist Luis McManus painting on some projects. Did you ever undertake any matte painting during your time at PU?

JD: Luis McManus did some paintings for JACK THE GIANT KILLER, but he did them for The Howard Anderson Company, as did Al Whitlock (who did three paintings that I can remember).

![]() |

| JACK, THE GIANT KILLER unused shot |

I did a very simple glass shot as part of an animation scene for JACK. The painting added a ‘roof’ to a cleft in the location rocks, turning it into a cave in which a chimpanzee was hiding (see frame at left). The entire scene was cut from the film—not because of the painting but because the editor didn’t want to establish the precise location of the chimpanzee relative to the giant and

the sea monster, who were visible outside the cave. This was one of the shots I designed and directed (on location) when it was decided to expand the fight sequence.

Later, I convinced Gene Warren to let me do an original negative composite shot for THAT FUNNY FEELING. I did the small amount of painting required by that shot.

Q: I understand that Gene Warren had some background in matte painting, or to be more precise, matte ‘blending’ -having been taught the ropes by the once legendary Jack Cosgrove while working for Jack Rabin and Irving Block on zero budget pictures in the 50’s such as MONSTER FROM THE GREEN HELL.

JD: I never heard so much as a whisper about that. As far as I know, all the Rabin-Block mattes were painted by Irving Block. Gene never revealed any interest in, or knowledge of, matte painting. He was primarily an animator—a very good one.

Q: Yes, Gene did some nice work in Tom Thumb as I recall. Project Unlimited were constantly in demand throughout the 1960’s. Were they perceived as being a sort of “ILM” of the day who weren’t afraid to tackle new and innovative effects that may have been outside of the sphere of the more traditional big studio visual effects departments?

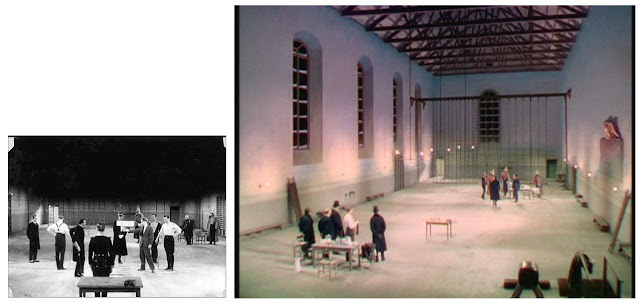

JD: Perhaps. The studios didn’t get involved in stop-motion animation much, so Project got a lot of jobs that required stop motion. Wah had a good reputation as a costume fabricator, so Project got jobs for Las Vegas shows as well as for film creatures. Project made dummies for SPARTACUS, Shields for THE WARLORD, and costumes items for CLEOPATRA. However, Project Unlimited didn’t do composite work, at least not initially. The really big effects work was done at the major studios, as when Buddy Gillespie filmed the submarine shots for ATLANTIS, THE LOST CONTINENT in the tank at MGM. MGM also handled the matte paintings for ATLANTIS. Project did only a few animation shots for that film..

![]() |

| A staff portrait of Project Unlimited - sans Jim. Photo from Jim's 2011 memoir 'Dinosaurs, Dragons and Drama' |

Q: With so many studios closing down their special effects departments in the early sixties I guess there were a lot of matte artists seeking work. The competition for freelance assignments must have been great?

JD: I wasn’t aware of any of that because I wasn’t trying to compete as a matte artist. The matte artist’s union kept refusing to let me join, so, whenever an opportunity arose to paint a matte, I just went ahead and did it secretly.

Q: So was the cave shot that was deleted from JACK THE GIANT KILLER your own first professional glass shot?

JD: Yes. Of those that actually made it up onto the screen, THAT FUNNY FEELINGwas my first.

![]() |

| Gigantipoids was a pre-production illustration for the last feature film that Jim contemplated, titled KRANGOA. (the family of ape-like creatures) |

Q: In your own matte art are you an oil painter or an advocate of acrylics?

JD: Originally, I painted all my professional mattes in oils. About 1975, I developed some sort of allergic reaction to the paint chemistry and had to change over to acrylics. That required a completely different technique and a re-learning process.

With oils, I blended skies by using cloth or polyurethane pads to pat the color after it had been brushed on in bold strokes. With acrylics, I found I needed to use a spray gun, with cross-hatching or stippling in some areas. My acrylic paintings (viewed in person) never had the impressionistic looseness of my oil paintings, but they photographed satisfactorily in most cases.

I’m now back to painting in oils without turpentine and without cobalt drier. So far, no allergy problems, of course, I’m now painting ‘fine art’ not mattes.

![]() |

| A full frame painting from PRINCESS AND THE GOBLIN |

Q: Take us through the typical time frame of the average glass painting Jim. How do you begin? Do you project a 35mm frame onto the pre-primed glass and trace from original first unit photography or do you approach it differently? Are there dip tests of short lengths of test negative and so forth? How many tests are on average required until a final acceptable match?

JD: There are many variables. First, only a few of my matte paintings have been done as latent-image composites. For those, I usually projected a developed film clip to trace off the blend-line position. If architecture needed to cross the matte line, those features were also traced.

Tests were made each day as the work on the painting progressed. Sometimes hand-developed dip-tests were made during the day to speed things up (but those produce only a monochromatic image). The number of tests varied. Usually, I could get a blend with four to six tests, but some jobs were problematic. I think I did about twenty tests for the MEMOIRS OF AN INVISIBLE MAN beach-house shot, because the lab was having problems and kept shifting my jobs to different printers. That caused major shifts in the overall color and made it difficult to evaluate the basic lay-in as to sky color. Then the editor wanted changes, and so on.

![]() |

MEMOIRS OF AN INVISIBLE MAN latent o-neg matte composite with the actual beach location seen at top. John Carpenter kept 'jumping' Jim's cue for action when he was running the safety footage at the start of each take. As a result, the test development required before each comp take (to be sure the 35mm neg is threaded on the correct perforation) showed that Ms. Hannah was already in action. It was Jim's last latent action take—sweaty palms on that one. |

![]() |

| The original matte painting for the above shot. |

For rear projection composites, I usually looked through the camera and outlined the painted area with a grease pencil, then painted a white underpainting [ground] before starting to work in color. For really critical alignments, I sometimes used a small 45-degree mirror in front of the matte camera to reflect a studio light placed 90 degrees to one side. If I saw the light superimposed exactly on the camera lens when I stood at the matte glass and looked back at the camera, I knew my light beam was on-axis. Then I could position my layout drawing on the glass by looking at the shadows my drawing was casting on the rear-screen image.Sometimes, I painted on dark “greylight” glass. This enabled me to put the process screen in contact with the back of the matte glass, so that there was virtually no parallax between matte glass and projected image. The light illuminating the painting was reduced in intensity as it passed through the glass and was reduced in intensity again when the resulting ‘fog’ on the screen bounced back toward the camera.

But the image from the rear projector was reduced only once on its way to the camera. Furthermore, the light on the painting went through the glass at an angle, making the light path for the ‘fogging’ light longer than for the rear-projected image, with the result that the glass had greater dark density for the front lights than for the rear-projected image.

Once proper filtration had been established for the system, the paintings could usually be balanced by eye, but some critical matches required film tests.

I did one two-projector composite with very little painting over one weekend, after an initial wedge test.

Q: I’ve always been of the belief that a successful matte shot can only be as good as the cinematographer shooting the plate and tying the composite together. Is that too simplified a statement do you think?

![]() |

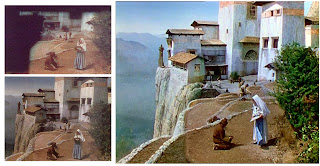

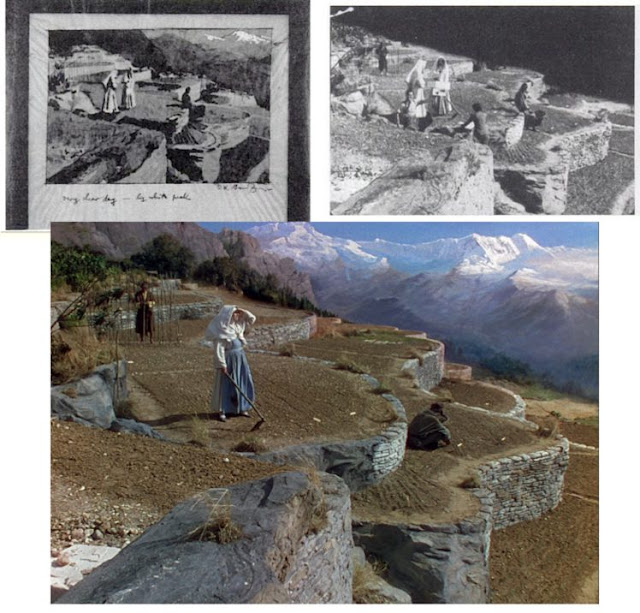

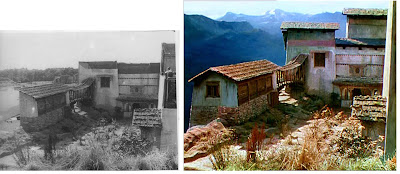

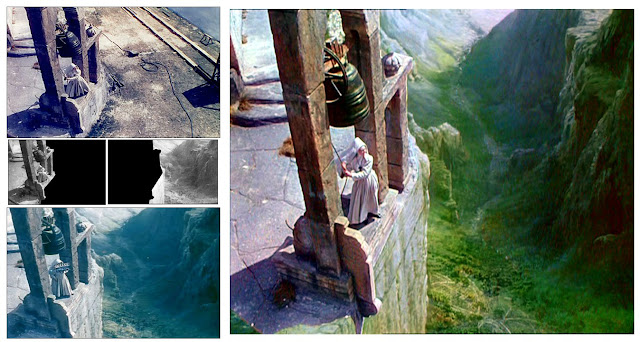

| Hilltop monastery painting for the action film NINJA III |

JD: I think so. First, I distrust having cinematographers “tie the composite together” unless it’s someone like Bill Taylor who completely understands what’s required. When a creative camera person is required to sit all day doing nothing while the matte artist paints, then finally gets to ‘do his thing’ when it’s time to test the painting, there can be a tendency to get ‘creative’ with the photography rather than just shooting at the established settings. When the matte artist sees the test composite the next day, the artist has no way of knowing whether any problems are due to artist errors or to unauthorized ‘adjustments’ by the cameraman. That’s when the artist may find it necessary to test the cameraman by doing nothing to a particular area of the painting, just to see whether it reproduces the same way as on the previous test.

It’s really not the job of the camera person to ‘tie the shot together’. The matte artist is responsible for the marry-up. In most cases, the camera person is responsible for only the dupe and maintaining it’s consistency (unless one is foolish enough to be making the composites on an optical printer by using filmed black mattes and counter mattes).

I agree that the success of a shot may depend in large part on the original photography. I have had to do some very ingenious ‘corrective’ printing to rescue live-action photography that was underexposed by the cameramen—even very good directors of photography. I was able to do this on one occasion by bi-packing a ‘plus-density’ mask that restored shadow density on a shot that had been underexposed. That may seem backwards, because “underexposure” sounds as though it would make the shadow areas darker. Film has a limited density. When a scene is underexposed, The highlights and mid tones get darker, but the ‘blacks’ don’t, When the mid-tones and highlights get corrected back to a normal density, the ‘blacks’ become grays and require additional density to be added synthetically.

On another occasion, I had to print the projection plate with a special traveling matte that lightened only the underlit actors in the foreground. In a similar case, I had to use a traveling matte to enable me to print the characters in shadow at one exposure and the meadow behind them (in sunlight) at an exposure that brought the two portions of the scene into a better balance. All that must happen before the painting can be started. If the artist doesn’t get these problems ironed out at the start, the artist can sometimes end up “Chasing the Dupe”—a phrase I first heard from Matt Yuricich.

![]() |

| An FX shot from the 'Hard Water' episode of the tv show SALVAGE 1 with painted iceberg and Whitlock inspired 'slit gag' effects for the approaching missiles. |

Q: I recently asked Matthew whether he recalled any ‘issues’ arising from whether a matte shot was controlled by those in charge being actual painters, such as Sersen and Kellogg as opposed to mattes being under the control of purely cameramensuch as Bill Abbott or Clarence Slifer. In Matthew’s day there was a definite ‘cohesion’ when artists and painters were running the show compared to when technical people such as cinematographers and non artistic types running the show. Anything in that Jim?

JD: I would always bow to Matt’s superior experience, but as it happens, I agree with him completely.

Q: I think you’ve tried to shoot as many of your own mattes personally. Is that right?

JD: Yes, for the reasons I just stated. Plus, some of my procedures involved animation at the time the painting was being filmed. It’s also less expensive.

![]() |

| A 16mm latent-image matte painted comp from Jim's THE PRINCESS AND THE GOBLIN reel. |

Q: Tell us how you met and became longtime friends with Albert Whitlock?

JD: I met Al in 1959 when I visited Peter Ellenshaw at Disney studios. Al was at work on a house painting for POLLYANNA, which I think was a latent-image shot.

I ran into Al again several times when he was painting for JACK THE GIANT KILLER at The Howard Anderson Company.

![]() |

| Painting a foreground glass for PAUL BUNYAN |

Later, I purchased an option on a short story entitled

“The Head Hunters.” I worked up a presentation of storyboards and artwork that included a large, framed oil painting of a key scene from the film. I showed it to a Jim Pratt in the production office at Universal. He was more excited by the painting than by the story, and he told me Al Whitlock was looking for an apprentice. I was reintroduced to Al and put on the Universal payroll (at a reduced salary compared to what I made when doing animation and miniature work).

That job lasted only about a month, because Al got into a conflict with the Universal management about how to charge off my salary (Al was afraid that if my salary was charged against his matte shots—of which I was not yet painting any—he might lose out on jobs). But Universal kept me on the payroll and shifted me to another part of the art department. Al and I remained on good terms, and we began to discuss a project that each of us had been intrigued by independently: THE LOST WORLD.

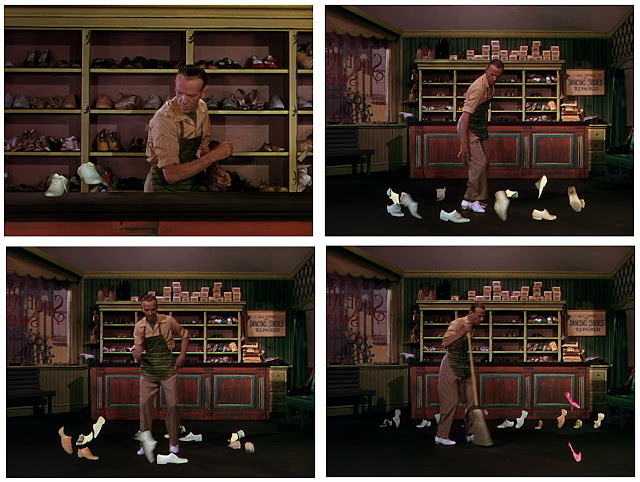

In addition to staying in touch with Al and having dinner with him and his wife on numerous occasions, I worked for Al again during I’D RATHER BE RICH (stop-motion animation of shoes) and, years later, when he was at work on DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER and was also doing matte shots for the GUNSMOKE TV series.

Al recommended me for several of the jobs I did over the years.

Q: I’d love to have seen that Danforth-Whitlock LOST WORLD.

JD: I thought I would too. However, as the years passed, Al realized that the dinosaurs would inherently be more memorable than the matte paintings, so he took over the creation of the dinosaurs, and I was out.

![]() |

| Another PRINCESS AND THE GOBLIN matte shot. |

Q: Even right up to his retirement from Universal Al was still hoping to make LOST WORLD I believe. Albert took on many independent matte assignments, especially in the early sixties. Butler-Glouner used Al on several films, always uncredited. Did effects shops such as Butler-Glouner, Howard Anderson and Van der Veer have their own matte painting facilities do you know, or were the glass painting always prepared elsewhere?

JD: The independent houses usually had a way to photograph the paintings, and a matte artist doesn’t take up much space. I think Al painted at home on the Butler-Glouner jobs and on some of the Howard Anderson jobs. But, on occasion, Al painted at Howard Anderson’s facility on the old RKO lot in Hollywood.

Q: I think many of those Poe films from American International such as PIT AND THE PENDULUM and I think COMEDY OF TERRORS used Al’s talents to great effect. I’ve often wondered too about another Butler-Glouner show THE DEVIL AT 4 O’CLOCK which has several mattes that look very much like Albert’s.

JD: I never asked about THE DEVIL AT 4 O’CLOCK.

Q: Terrible blue screen work with Spencer Tracy’s silvery hair becoming totally transparent at times due to blue spill or problems pulling the mattes. Great Larry Butler miniatures though and some pretty bold epic composites shots for the time.

JD: The miniature volcano was built in large scale on Butler’s ranch. It’s been said that Larry wanted a lake on his property, and dredging out the dirt to build the volcano was a good head start.

![]() |

| THAT FUNNY FEELING - An actual LA Freeway masked plate and the miniature of the traffic congested opposite lanes complete with off the shelf toy cars and some subtle glass painting to tie the model and location elements together in a brief tour de force effects sequence that is simply wonderful. |

Q: I’m very interested in one particular project you undertook, THAT FUNNY FEELING, which although a Universal film with photographic effects by Al Whitlock, your own contribution was through Project Unlimited as I understand it. The opening LA freeway traffic jam effects shot was a stroke of genius Jim, not just in the wonderful stop motion, but also in the precisely calculated camera elevation done back at Project Unlimited on the miniatures as well as the flawless blending of live action freeway against your impeccably lit and photographed miniature set. One of your best effects shots ever. Would you like to tell us about that?

![]() |

| Frames from the final original negative composite with stop motion traffic perfectly lit, photographed and blended with the live action plate. One of Jim's best ever effects shots where each and every aspect falls into place with precision. |

JD: I was actually involved with two shots for THAT FUNNY FEELING—the head-on train crash, for which I painted a large sky backing and the traffic-jam shot you mentioned. My main contribution to the traffic-jam shotwas to steer Project Unlimited away from their plan of turning the element over to some optical department to composite (no more giant matte lines, thank you). I composed the shot, placed the black matte in front of the live-action camera, and did the minimal painting and the primary animation. Other animators handled the background cars. Ralph Rodine did the lighting and camera work. We looked through a film clip of the live-action scene that was placed in the movement of the animation camera, then moved the miniature set and the camera around until it matched the perspective of the real freeway lanes. When the shot was finished, Gene Warren took it to Universal, where they spliced it into a loop and screened it over and over, pondering how it had been done. Not bad for my first professional latent-image composite.

![]() |

| The miniature head on train collision by Project Unlimited from THAT FUNNY FEELING with Jim supplying the painted sky backing. |

Q: Not bad!……it was technically and artistically as good as it gets Jim. Definitely one for the showreel and to be proud of. Unfortunately I don’t know anyone who’s ever seen the film aside from me?

JD: Well, of course I went to see it. It was exciting to realize that, right in the opening sequence with the trains and the cars, there was also a great Al Whitlock painting of a New York Street. My work was in good company.

Q: As photographic effects supervisor, was Albert in any way involved in the design or ‘look’ of that shot, or was it totally sub contracted?

JD: No, Al was not involved at all, except for the fact that I had recently worked with Al and felt comfortable about doing original negative work.

Q: You secured a short term apprenticeship in Whitlock’s matte department around 1965, which I imagine was an eye opening experience for you? Can you share with us some of the effects work Al and his team were working on at the time?

JD: As I recall, it was in 1964. MARNIE was in work at that time. I think SHIP OF FOOLS followed soon after. THE WARLORD was on the planning boards in the art department, but no filming had been done and Al hadn’t started on the mattes yet. I visited Al during the time he was working on mattes for THE WARLORD.

![]() |

| From THE HIT MAN, a TV movie and pilot for Columbia. Danforth added scintillating light patterns in the glass columns. It's all painted except the trapezoidal room and walkway. |

Q: I’ve heard that one of Al’s mattes around the time you were there, the one of the ship docked with city background for MARNIE was reallydisliked by the head honcho’s at Universal for some reason and they requested Al pull those shots from his showreel. Can you elaborate?

JD: Yes, apparently there was a general dislike of that shot (and all the matte shots from MARNIE). I thought it was a particularly nice shot except for the improbable ‘God’s viewpoint’, which Hitchcock seemed to use in several films. (What is the camera supposed to be supported by?) I think the real problem was with a dreadful ship cut-out in a forced perspective set used for lower angles. Perhaps viewer complaints about a dreadful ship shot were not interpreted correctly. If I owned that Whitlock painting, I’d proudly hang it on my wall. The effect of afternoon light was beautiful.

Also for MARNIE Al painted the interior of a tithe-barn stable with a bright glare of light coming in the window. The glare was very impressive. It was just a thick streak of pure white paint). The specific shot Al was primarily working on when I arrived showed Sean Connery and Tippi Hedron walking to the barn. Al pointed out that the shake roof of the barn was created by alternating lines of reddish and greenish shades of gray.

Q: That barn interior tends to slip by totally unnoticed. The thing looks like almost all of it’s Al’s paint excepting the actors and horse? Can you recall it?

JD: My memory is that the painting showed the entire interior of the vaulted, beamed ceiling, plus the top third or so of the support columns. My guess is that there was action filmed in the foreground of the set—later edited out—and which required more of the interior to have been constructed than would have been necessary for the shot as it was finally edited.

Q: According to Bill Taylor quite the opposite occurred with COLOSSUS-THE FORBIN PROJECT where the studio brass were over the moon with that amazing ‘super computer boot up’ matte set piece and were keen to show it off. Apparently that was Al’s most difficult shot from what Rolf Giesen told me. I think it’s one of his best – and all on original negative too!

JD: Yes, very impressive. Al said that he missed the precise timing from his stop watch by about eight frames. That’s so close that no one would notice the ‘error’.

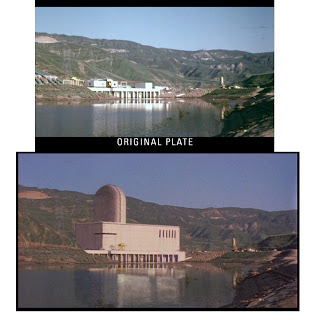

![]() |

| Whitlock's 95% oils / 5% real COLOSSUS matte shot |

I also liked the shot of the couple sitting in mountain shadow on a lookout point above the distant Colossus facility in the sunlit valley below. To get that effect, Al had the grips build an ‘awning’ over the young couple. Al then matted out everything except the shadowed couple, a few feet of fence, and a little of the sunny valley beyond them. Then he flawlessly surrounded them with the painted valley and the colossus facility.

Q: I have a before and after on that matte shot. The amount of paint is remarkable. It must have been something like 95% Whitlock and 5% genuine set! I think that must have been something Al possibly picked up from Peter at Disney – not to get fiddly with demarcations and preserving most of the ‘real’ set – just paint the whole damned thing, which Ellenshaw was a genius at. So many of his Disney shots were ALL paint –right around into the immediate foreground with incredibly courageous brushmanship. Peter would just ‘slot’ in the actors somewhere amid all that oil paint, and to beautiful effect. Things like DAVY CROCKETT and JOHNNY TREMAIN are wonderful examples of this “ballsy” approach which most wouldn’t have the guts to tackle.

JD: That’s certainly true. Of course, the projection system used at Disney made it easy to place the actors and a small envelope of background into the paintings. (I once had to totally alter the set an actor was standing on, when the director decided to change the shot design after the live-action was filmed. You can’t do that with a latent-image matte.) Al didn’t like the rear projection system, and he managed to do shots of type you’ve described with latent images. But then he usually had great control of the photography and shot design.

![]() |

Just when you thought mattes couldn't get any stranger... A full painting of a baseball stadium Jim did for a heat pump commercial. The idea was that heat pumps could be used to condition the air of many different kinds of buildings. Jim painted four different buildings—all designed to somewhat resemble the outside configuration of a back-yard heat pump. Jim also lit and filmed the actual product heat pump, then projected the contours onto four glasses and painted a 'bank' heat pump, a 'drugstore' heat pump, air 'airport-hanger' heat pump, and the 'stadium' heat pump. All but the stadium had live-action that needed to be blended in. |

![]() |

| The 'Bank heat pump'... |

![]() |

| The airport had two sections of live action (workers in the hanger and an airplane coming in for a landing, which Danforth created on film using a bas-relief plane on a sliding glass. The stadium had moving crowd effects. All four of the paintings were connected by dissolves made by Jim in the camera. This short-schedule job was completed with a forty-hour non-stop stretch of work, during which Jim's wife Karen brought him breakfast, lunch, dinner, etc. Some of the work (like pre-filming the plane landing and all the color balancing of the projection plates had been done prior to that. Jim also filmed the background plates and printed them prior to that. |

Q: Didn’t Albert even ‘pirate’ some classical gallery masterpieces in his spare time so that his old pal Alfred Hitchcock could have duplicate paintings?

JD: Hitchcock maintained two homes, but the original masterpieces in Hitchcock’s collection could be at only one location at a time, so ‘Hitch’ asked Al to duplicate the classic paintings.

Q: A friend of mine in Germany (who’s also a big matte fan) actually owns an original Whitlock gallery piece, and it’s exquisite Jim. Lucky guy!

JD: One of my regrets is that I never asked Al if I could acquire one of his paintings. He had two hanging in his home that I particularly liked—a view of the ship Cutty Sark under full sail, and a scene of a stately English home in late afternoon light.

![]() |

| One of those "invisible" mattes— basically a split screen with only a little painting to make it blend. THE SHADOW RIDERS. Tom Selleck, etc. were filmed in Sonora, California, some miles from the ocean. |

Q: Virtually nothing has ever been written on Al’s long time cameraman, Ross Hoffman, who had been with the studio since the early thirties non stop through to EARTHQUAKE in 1974 – by all accounts, an amazingly versatile and skilled cinematographer who occasionally got an on screen credit. If you can, please tell us more about Ross?

JD: I don’t know too much more about Ross, I talked to him a lot when I was working with Al or visiting him at Universal, but mostly I asked Ross technical questions, not about his career, per se. Ross showed me the set-ups used for printing the rotoscoped mattes that were the norm at Universal for years. The mattes were painted on cells, using opaque white paint. The cels were placed on a frame with registration pins that was positioned between an optical printer and a large studio lighting unit. With the lighting unit on, the silhouetted cel formed an aerial-image matte, printing the background scene threaded in the printer but leaving an unexposed area for the element to be added. When the lighting unit was turned off and the cel was illuminated from the front, the cell printed the portion of the live-action scene that was being matted into the duped background.

Q: I just think back to the huge numbers of mattes and opticals that Ross put together over 40 years and my mind boggles. Aside from his many ingenious black velvet density matte opticals for all the INVISIBLE MAN sequels for John Fulton, his truly phenomenal SON OF DRACULA mist morphing transformation optical effect has to be one of the all time great trick shots.

JD: I’m not a big fan of horror films so I can’t contribute anything to that topic.

Q: Maybe so, but Ross was definitely one of Universal’s unsung heroes who more than earned his keep. Gee Jim, how can you not love TARANTULA or THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN?

JD: like THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN, but I don’t care much for TARANTULA as a piece of drama, and then some of the mattes are ‘keyed’ incorrectly, with the result that the spider doesn’t always fit behind the rocks correctly.

![]() |

| A full painting which functioned as the background for a THEY LIVE travelling matte shot (a shot I could never locate in the DVD myself??) |

Q: It’s such a shame that the authors of the excellent book The Invisible Art – the Legends of Matte Painting didn’t interview Hoffman who lived on into the mid 90’s. Can you tell us anything at all about the longtime rotoscope artist, Millie Winebrenner who was also a mainstay at Universal for decades from those 50’s sci fi pictures through to EARTHQUAKE or THE HINDENBURG I think?

JD: I met Millie but didn’t really know her. I had worked closely with her former assistant, Nancy van Rensellaer during JACK THE GIANT KILLER. The hand-drawn mattes at Universal were created on special drawing tables that had camera/projectors under them, projecting from the bottom the image to be traced. This eliminated the shadows of the artist’s hand that occurs when the scene is projected downward onto a drawing table from above. At Universal, when the cells had been painted and were ready to be photographed, the camera/projector was rotated from below the drawing table to a position above the table, permitting the artwork to be photographed. Sounds like a major engineering challenge to me, but it obviously worked.

![]() |

| One of the mattes painted and composited by Jim for the tv series SALVAGE 1. Several of the shots involved a sliding painting of the giant moving iceberg augmented with artificial 'wake'. The sea is a plate of the Pacific Ocean and the tugboat is real. Additional shots were achieved by Harry Walton with stop motion animated miniatures and process projection. |

Q: Al once wrote for American Cinematographer that Millie used to paint full size sheets of glass for some roto shots against his paintings, requiring sometimes 70 or so individual full sized matte glasses for a single pass in the days before cels. That must have been some major undertaking?

JD: The use of glass seems odd, since ‘cels’ have been around since before Al Whitlock started painting mattes. Perhaps it was due to the heat of the lights. I remember that when Al first told me he was going to try rotoscoping live action and matting it in front of his paintings using out-of-focus cels, I was dubious, because when I had asked Nancy van Rensselaer to make cels for an animated spilt screen during JACK THE GIANT KILLER we had gotten a very noticeable dark matte line because Nancy didn’t make complimentary cels with a gap between them as I requested (usually necessary when doing out-of-focus splits against light backgrounds). I know that, initially Al planned to use only one set of cels. I don’t know how he solved the non-linear reproduction of out-of-focus images. One of Al’s tricks was to film the actors in front of a crudely-painted backing that had colors and tones similar to the matte painting in the area behind where the matted actors would appear. That way, the slight intentional oversizingof the out-of-focus matte would not clip into the actors but would blend with the background. It certainly worked well.

![]() |

| A pair of fully painted matteshot frames from John Carpenter's PRINCE OF DARKNESS. The top image is a somewhat discoloured clip in Jim's collection that I have deliberately included here as the unique sun and moon view is clearly seen, whereas the release print as transferred to DVD below tended to 'blow out' all of the highlights, completely obliterating the whole narrative point of the matte painting. Having compared the two images Jim leans more toward the upper frame as being closer to how he recalls painting the shot. Jim commented: "I saw the preview screening of PRINCE OF DARKNESS, and I would have gone ballistic if the scene had been printed like this second frame version. My version still has a little too much green lurking around the sun, but it's MUCH closer to what I did for the film. The overall tone was cool, not warm." This goes to show just how shots can and often do show up vastly different on varying viewing platforms. |

Q: I found out recently that both incoming andoutgoing Universal matte painters, Al Whitlock and Russ Lawsen respectively, painted on the same 1962 feature – TARAS BULBA, which was Lawsen’s only on screen credit that I’ve ever been able to find. The photographic effects were split between 3 providers: Universal, Butler-Glouner and Howard Anderson, so I’m not sure just where Whitlock fitted into this jigsaw puzzle as he worked for all three. Al painted those chasm shots while Russ handled the city paintings I’m told by Al’s friend Rolf Giesen.

JD: All I can add is that I saw one of Russ’s TARAS BULBA city paintings at Universal around 1964. But I recall that Howard Anderson was involved with some of the chasm scenes, so it’s possible that Al painted for The Anderson Company on TARAS BULBA.

Q: I’ve never met nor read accounts from anyone who has actually seen one of Lawsens’ paintings, at least someone who’s still around. I don’t think even the authors of that terrific matte painting coffee table book came across any of them. I asked Bill Taylor whether any of Lawsen’s mattes still existed at Universal and he told me that by the time he had joined in late 1974 there were no mattes that pre-dated Whitlock’s work. My readers would be most interested in your memories of Russell’s matte if you can stretch your memory back that far Jim?

JD: Regarding the Russ Lawson painting: It didn’t make much of an impression on me. I remember it as being smaller than Al’s paintings. It wasn’t stashed in the back somewhere. Al just reached down and lifted it up from somewhere near by. It seemed to be ‘flat’ in terms of reflectivity, but that may be a trick of my memory. Al’s paintings always seemed glossy (because they were). I’m sorry I don’t remember more, Peter. Like many things I’ve encountered through the years, if I’d known it was going to be of interest later, I would have paid more attention. It was a wide view of a city.

![]() |

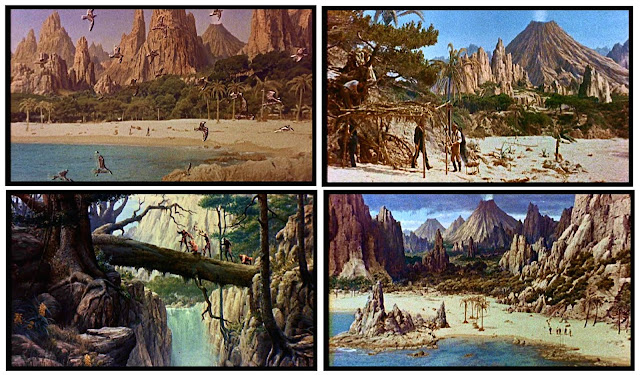

| An excellent example of Jim's rear screen process as applied to composite matte photography - with this scene from PLANET OF THE DINOSAURS. |

Q: I remember a fascinating story you told at the Visual Effects Society a few years ago for their tribute to Albert about his need to “fix” a certain SHENANDOAH matte painting – even though it was some time after the film had been released. Would you like to expand on that Jim?

JD: Apparently there had been something about that SHENANDOAH shot that Al felt was not right, even though he had approved it for use in the film. Later he realized what the problem was and pulled the glass out of the storage rack and quickly made a correction. As I recall it was a matter of the brightness of a house in the distance. Al lightened it with a few deft strokes, stood back, looked at the painting and was satisfied, at last.

Q: Can you remember the shot? There were around six mattes in that film – one of the many shows he painted on for director Andrew V.McLaglen.

JD: It’s the last one in the film.

Q: Oh yes, I know the shot very well – with the horsemen crossing the stream to the farmhouse, right? Would you tell us the most valuable lesson(s) you learned from your time with Albert?

JD: That’s complicated. I cover that at some length in my memoir. But in essence Al taught me to “befearless and to paint thetruth”.

![]() |

| Composite shot from THE STUFF. The McDonald's stand is entirely a Danforth painting. The other buildings are miniatures (because they blow up). Jim designed this shot while his company Effects Associates hired the 'extras',and filmed them in the parking lot of the industrial complex where they were located. Jim directed the shot and did the composite. (all rear projected.) |

![]() |

| The Effects Associates crew with miniature set for THE STUFF |

Q: Bill Taylor said that Al always painted very “flat” – avoiding any build up of excess paint which might cause shadows or pin points of light.

JD: Yes, the glints from the micro bumps in the paint were sometimes a problem for Al. One of my first assignments for Al was to scrape down the surface of one of his paintings, using the flat edge of a razor blade, so Al could repaint that area. That was fairly daunting, but it didn’t do as much damage to the painting as I thought it might.

Q: I shudder at the thought Jim….new ‘green’ matte assistant armed with razor blade and doing his utmost not to do the unthinkable?? Must have been a palm sweating occasion?

JD: first time I did it I was very worried.

Q: Come to think of it, I can recall several old time mattes, always colour shows, where ‘glints’ and ‘pops’ seemed incongruous with the painted part of the scene – especially in night skies.

JD: Yes, it’s always difficult to get the lights at an angle where that doesn’t happen—probably impossible. Of course polarizing the light helps (as is done in cartoon cel photography) but a lot of light gets absorbed by the polaroid filters. During EARTH II at Fox, we oiled Matt Yuricich’s star-field paintings immediately before photography. This helped eliminate any specks of dust that would show against the black of outer space.

![]() |

| A wonderful example of Jim's fine art - THE NAUTILUS UNDER CONSTRUCTION was painted for fellow Cascade staffer Tom Scherman. Some time later the painting was returned temporarily to Jim for some artistic changes, at which time Scherman sadly passed away. The artwork is now owned by miniature pyrotechnician Joe Viskocil. |

Q: To the best of your knowledge, was the original negative matte process utilized elsewhere at that time or was Al the only real advocate of the method?

JD: Disney did someoriginal negative mattes on occasion (as in the shot in which Sean Connery and Janet Munro run down the hill in DARBY O’ GILL). I had done a 16mm latent matte composite test earlier, and I started doing it again after working with Al.

Q: Some effects departments such as MGM were staunch advocates of that complicated duplicating stock process weren’t they – the method later adopted by Doug Trumbull and co for Matthew Yuricich to use on all of those projects?

JD: I think you are referring to color interpositive dupes a.k.a. color intermediate stock dupes. There may be some confusion here as to the complexity. Running a single interpositive is less complex than running three black and white separations in three separate passes—less complicated for the cameraperson. However, for the artist, color interpositive dupes could be difficult, because that stock ‘skewed’ the colors and contrast of the painting.

Clarence Slifer at MGM had an interesting variation on the use of this stock. That variation originated before IP stock existed, when Slifer used positive Technicolor prints to dupe certain elements during GONE WITH THE WIND by photographing the aerial image formed by what amounted to a projector without a lamp house. Later the interpositive stock yielded a better color reproduction than duplicating a viewing print. It was also easier to repeat moves twice instead of four times, as would have been necessary if color separations had been used. Clarence’s big ‘gimmick‘ was using the precision lens-move capabilities of an optical printer without a lamphouse to scan across the film being duplicated, and to then repeat the same moves with the interpositive and the printer movement removed from the printer, this time photographing only the painting. The duping and hold-out mattes could be on a foreground glass (for soft blends) or incorporated into the painting as a clear area, through which a white duping board was photographed with the painting in silhouette. Or through which a black background was visible while the painting was illuminated and being photographed.

Not many studios used aerial-image dupes (although those were popular for cartoon work). More often, inter-positive stock was bi-packed in a standard matte camera, but moves on paintingscould not be made that way.

![]() |

| One of Jim's mattes from the film BUGSY. |

I did only two shots on interpositive stock. I found it very exasperating, because the contrast of the duping stock is 50% higher than camera negative, so the paintings had to be painted in low contrast (and in ‘odd’ colors sometimes). Matt Yuricich was a master at this.

Q: Poor Matthew had to be!

JD: Yes. He occasionally complained about the fact that he was obligated to use that system in many of his employment situations. I remember him saying that, to get the right shade of green trees he had to paint in “baby-shit brindle brown” tones

Q: Yes, I’ve heard that delightful turn of phrase from Matthew. I don’t think Windsor& Newton have that particular hue on the market any longer! I sure don’t have any in my box of oil paints.

![]() |

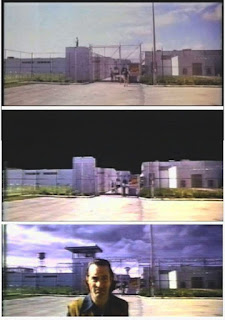

| Jim's painted prison complex as seen in the excellent under rated Jon Voight film RUNAWAY TRAIN |

Q: Film Effects of Hollywood has been a major contributor on the LA effects scene for many years and I know you worked there for a time on IT’S A MAD, MAD, MAD WORLD. Linwood Dunn had a long history at RKO with Albert Maxwell Simpson – did you happen to know Simpson by any chance? I ask because there is so little known about the man and he was one of the veteran artists who, like Jan Domela who had an epic length matte career spanning way back to the twenties. I learned recently that Simpson painted some of the many glasses on KING KONG, along with Henry Hillinick, who was Matt Yuricich’s mentor.

JD: No, I didn’t know Simpson, unfortunately.

Q: Bill Taylor told me of a wonderful Al Simpson oil painting which used to grace the wall of Linwood Dunn’s office at Film Effects of Hollywood. Do you recall that?

JD: There was a painting from THE GREAT RACE that Lin said had been painted by Simpson. That was on the stage and showed an Alaskan dock and trading post. . In the front hall of Film Effects was a large painting from WEST SIDE STORY. I don’t know who painted it.

By the way, the most impressive painting I ever saw hanging in a Hollywood office was a western landscape done by matte artist Jack Shaw (but this was a fine-art painting). It was in the office of Producers Service Company—suppliers of optical and effects equipment.

Q: Yes, Jim Aupperle has that GREAT RACE painting now, though the previous owner sawed off the black matte across the lower area. A nice painting though. Jim sent me some great close ups of Simpson’s brush work from that one. That show was jammed with good matte art. On Jack Shaw, I wonder if that painting you referred to was one of the ‘War Eagles’ conceptual oil paintings which Harryhausen spoke of as being “still around somewhere”? Apparently Jack painted a couple which totally impressed Ray and Willis O’Brien!

JD: The painting at Producers Service Company was a view of a western plain, so don’t think it was for WAR EAGLES. Perhaps it was something done for GWANGI, but I tend to think it was art for its own sake.

![]() |