Greetings fellow matte shot enthusiasts. I'm back with what will, hopefully, be another enthralling and informative look at that magical artform we commonly know as the traditional matte painting. This time round I'll be examining the fascinating world of what could possibly be considered the purest and least adulterated of all camera effects tricks, the foreground glass painted effects shot.

However, just before we embark on that journey, I have a request:

To my readers out there. I'm always looking for articles or clippings on traditional special effects and would always welcome scans of articles of interest and such from journals such as old, old issues of American Cinematographer, Cinefantastique, Journal of SMPE or any industry or studio trade journals that may have effects info or interviews. I'm not the in the least bit interested in current era technology nor those same tiresome so-called 'effects driven' films for that matter. I do get some great material occasionally from a few international readers (you know who you are Federico and Stephen P), and it's greatly appreciated. As an example, I recently got a hold of many issues of 20th Century Fox's own in-house magazine, Action, from the 40's through to the 50's, from which some terrific matte and miniature info and pics were seized upon. Contact me if you can help... it all goes toward making Matte Shot even more fascinating than it already is (is that even possible??)![]()

![]() |

| Glass shot from Warner's A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM (1935) |

I have accumulated a huge amount of fascinating imagery for today's blog which demonstrate with impressive results, just how commonly utilised the glass painted shot was from the beginning of motion pictures right the way through to much later, more sophisticated era's when the old time method could still pull a few tricks on the movie going audience.

In addition, I'll be demonstrating a number of excellent examples of a well established variation upon the standard glass shot technique whereas the required matte painting is rendered on plywood or sheet metal which is then carefully cut out and mounted in front of the camera. The materials might be different, though the method is essentially the same and was the preferred

modus operandi among some masters of the artform, particularly among European effects men. The shots I've selected are amazing.

This admittedly sizable blog article comprises a number of 'chapters' if you will. I've broken down various aspects into important sub-headings as I want to contain it all in the one blogpost and never really enjoy breaking these things into subsequent monthly installments as my mind tends to wander and I'm generally focused on an entirely fresh topic. With today's blog I feel it's essential to break down the info as thus:

1. The Early Days of The Glass Shot Technique - where I'll look at the Hall Process and Norman Dawn etc. Some great rare material here.2. The Glass Shot in England and France - where the contributions of Walter Percy Day are discussed.3. Glass Painted Shots of the 1920's in Hollywood. 4. The Thirties and Beyond - the Era of Sound & Colour.5. Fox Raises The Benchmark. Wonderful examples of how sophisticated the technique became under 20th Century Fox's creative Fred Sersen / Ralph Hammeras matte department. Some jaw dropping shots here!6. The Maestro - Spain's Emilio Ruiz del Rio. One of the true masters of the medium for more than 40 years. 7. Other Glass Shots. A large selection of assorted shots from fx artists such as Jim Danforth, Les Bowie, Mario Bava, Matthew Yuricich, Jiri Stamfest, Leigh Took, Robert Skotak, Ray Caple, Peter Ellenshaw and others.![]() 8. Glass Shots in the Digital Era? Yes, there is still life in the 120 odd year old methodology yet, as you will see.If I knew how, I'd make a gadget so that the reader could 'click' straight to a given 'chapter', but alas, just typing up these bloggings is an ordeal for moi.

8. Glass Shots in the Digital Era? Yes, there is still life in the 120 odd year old methodology yet, as you will see.If I knew how, I'd make a gadget so that the reader could 'click' straight to a given 'chapter', but alas, just typing up these bloggings is an ordeal for moi.

Glass painted photo effects had been occasionally used historically to enhance and expand artistic expression in commercial still and portrait photography as far back as the mid 19th century. The advent of motion picture technology in the latter years of that same century would see a number of photographic tricks formerly associated with still photography such as multiple exposures, specialist laboratory processing and in camera 'live' visuals such as glass painting being adapted and freely experimented with by moving picture exponents.

![]()

For movie producers, the application of the glass shot was even in the infancy of moving pictures, a highly versatile, economic and boundary expanding process whereby the only acknowledged drawback was the time taken up on set as the matte or glass shot artist painted in whatever the art director desired as cast and crew sometimes were kept waiting. The glass shot process - or more correctly it was termed

'glass work'during those early decades - offered superb

first generation latent image composites in camera as the entire scene involving the painted glass and the live action was filmed and unified as one live onto the original negative.

![]()

Essentially, the typical glass shot comprised of a large sheet of clear glass bound within a sturdy wooden frame. This heavy framed glass plate would be well secured onto a rostrum of some description, sometimes with a purpose built 'shed' of sorts built surrounding the glass (with the glass more or less acting as a window). The darkened 'shed' acted as a shield against unwanted reflections that might be cast upon the glass during filming. Some glass shot artists just utilised a black canvas tent over the top of the glass and work area for the same purpose, especially when shooting outdoor glass effects. Depending upon the matte artist, some would illuminate the artwork purely with available daylight, which of course perfectly matched the Kelvin (light temperature) of the live action at the time. Others would use artificial lights to illuminate their painting, or at least to bring it up to the same 'levels' as that of the action being filmed through the clear areas of the glass.

![]() |

| An Emilio Ruiz glass up close. Note the modern streets of Madrid under it. |

Naturally, the glass shot was never a full, complete painting. The purpose of the glass matte painting was to 'fill in' whatever parts of the shot the director required, leaving often significant portions of unpainted clear glass through which the actors could do their thing whilst carefully staying within a prescribed set of marks in order that they don't vanish

under the painting. The beauty of the technique was that the finished effect was always100% first generation, and by the end of the satisfactory take, would be 'in the can' as it were. All done, "cut and print... now lets move on to the next set up."

![]() |

| Norman Dawn |

As far back as the early 1900's the process was in demand, with several practitioners in that field gainfully employed. Most notable of these men was pioneering film maker, cinematographer, newsreel maker and photographic effects artist

Norman Dawn (1886-1975) who is generally acknowledged as being the inventor of the glass shot process, as adapted from his early days in commercial photography as far back as 1905. Dawn's first use of the glass process as applied to the movie business is thought to have been in 1907 for the production MISSIONS OF CALIFORNIA.

Norman worked on some 800 or so matte shots, split screens, models and other effects throughout his lifetime, with a five year stint as matte shot expert at Universal Studios under Phil Whitman until 1921 and culminating in several years as matte painter under Warren Newcombe and Cedric Gibbons at the prestigious MGM in the mid to late 1940's on big films such as GREEN DOLPHIN STREET and 30 SECONDS OVER TOKYO. Norman managed to patent his matte shot process, though this wasn't without it's own series of courtroom headaches. Dawn would pursue his own film projects and take on various effects jobs until more or less retiring in the early 1950's. Dawn would maintain meticulous notes, photographs, 35mm nitrate film clips and journals documenting his very long career (some of which are illustrated here), much of which now reside in the University of Texas archive. Up until his death, Norman was still tinkering with motion pictures as well as illustrating childrens books.

![]()

Dawn's chief competitor in the glass matte shot stakes was

Ferdinand Pinney Earle (1878-1951) who, like Dawn, was something of an

auteur in as much as producing and financing several of own film projects, directing, writing and providing the special photographic effects. For a time Earle and Dawn were locked in legal battles over just who invented the matte process. A few years later, renowned Fox effects man

Ralph Hammeras would also patent the glass shot technique. Ferdinand had studied painting in the Paris atelier of the great William Bouguereau prior to getting into film work.

Creatively, Earle was ambitious and utilised glass and matte techniques to the fullest on his quite grand productions such as THE RUBAIYAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM (1923) where via camera magic Earle was able to lend much grandeur to the proceedings by all accounts. Long time chief matte painter for Warner Bros,

Paul Detlefsen, would get his start in the effects business under Ferdinand Pinney Earle on films such as DANCER OF THE NILE (1923) painting numerous glasses of temples and set extensions of ancient Egypt. Paul was a long time Hollywood matte specialist who's career spanned several decades until the early 1950's when he left it all to become a celebrated calendar artist in his own right.

![]() Walter G. Hall

Walter G. Hall was a British born Art Director who developed and patented the so-called 'Hall Process' in 1921- a variation upon the established glass shot whereby well rendered paintings (and later photographs) on sturdy cardboard were carefully cut out with a beveled edge and mounted in front of the motion picture camera to fill in studio sets. The technique was quite popular at the time, and like the standard glass shot, the director was able to view the finished effect immediately on the set rather than have to wait for weeks to see the first developed footage.

The aforementioned

Ralph Hammeras (1894-1970) was one of Hollywood's most versatile effects men, and could turn his hand to all aspects of trick photography, be it miniatures, camera effects, animation and glass painting. Ralph was the first ever technician to receive an Academy Award nomination in the field of special effects, or 'technical effects' back in 1928 for his glass painted effects for THE PRIVATE LIFE OF HELEN OF TROY (1927). Hammeras was a fine glass artist and his work can be seen in many films such as the original THE LOST WORLD (1924) right the way through scores of 20th Century Fox pictures such as CHARLEY'S AUNT (1941), DRAGONWYCK (1946), CALL ME MADAM (1952) and THE ROBE (1954). For a time Ralph was head of the Fox special effects department but according to Matthew Yuricich, was sidelined and more or less demoted for reasons unknown, with Fred Sersen taking the reigns. Later on Ralph contributed glass paintings to the low budget and sorely under rated (but really effective) BLACK SCORPION (1957) for Warner Bros as well as a key large in camera glass shot for the epic CLEOPATRA (1963).

![]() |

| Paramount artist Jan Domela with glass set up. |

Other glass shot artists in the business during the early days and on into the advent of sound pictures included matte painter

Irving Martin, who with cameraman

Paul Eagler produced glass shots at the Thomas Ince Studio from around 1915 through to 1925. South African born

Paul Grimm commenced his Hollywood career as a matte and glass shot artist in 1919 and worked on many early Warner Bros pictures such as NOAH'S ARK (1929). Grimm tired of the film business and quit in 1932 to take up full time portrait commissions and landscape painting.

Jan Domela painted glasses and mattes for Paramount from 1927 and worked an incredibly long career of nearly 40 years working on hundreds of pictures, usually with friend and cameraman Irmin Roberts.

![]() |

| Lewis J. Physioc - glass and matte shot expert. |

Lewis Physioc (1879-1972) was another in demand camera trick shot expert who as well as being an effects cinematographer and matte artist also published a number of academic articles on the theory and technique of cinematography. Physioc started as a scenic artist in 1914 and made the transition - as many did - to glass work and mattes right through the Golden Era at Columbia and Samuel Goldwyn with much of his later work done at Republic Pictures.

Other notables involved in glass work in those early days were

Albert Maxwell Simpson,

Byron Crabbe, Hans Ledeboer and

Mario Larrinaga with Simpson in particular enjoying a very, very long career in matte work.

![]() Neil McGuire

Neil McGuire is a name totally forgotten today but one who contributed much to New York based matte effects in the late 1920's with his associate

Warren Newcombe. Newcombe, of course, would go on to head MGM's industry famous matte department for some 25 years where the all round special effects standards were indeed the envy of Hollywood. Noted matte exponent Matthew Yuricich mentioned in his oral history of Newcombe bringing Neil out to Hollywood from New York, so I assume he may have possibly painted at MGM for a time. Warren painted mattes for D.W Griffith's AMERICA (1924) so I assume that Neil was also involved. The editor of Film Daily had this to say of Neil McGuire in an October 1931 issue;

"I spent an interesting hour with Neil McGuire yesterday at his studio over at National Screen where he is what you term a technical artist. He paints scenery, art effects, animated figures and atmospheric stuff and combines them with trick photography with live actors and gets some amazing effects on the screen...his stuff entirely replaces expensive sets, and with cunning camera work it takes an expert studio man to tell the difference."

British born artist

Conrad Tritschler is another name largely lost on most film students of today. Originally a theatre backing artist, Tritschler graduated into special effects work during the silent era and painted excellent glass shots for notables such as DeMille, Fairbanks and Carewe. Conrad's eerie glass work in the Bela Lugosi picture WHITE ZOMBIE (1932) was indeed memorable as were his miniature disaster sequences (supplemented with glass art) for FLOWING GOLD (1924), and I strongly suspect that he also painted the glass shots for Universal's DRACULA (1931) as well. Apparently Albert Whitlock was very fond of Conrad, so perhaps there was a British connection somewhere way back?

![]() |

| Walter Percy 'Poppa' Day glass painting for LA TERRE PROMISE (1925) |

Across the Atlantic the process was also alive and well, with early application of the glass process being devised by British set designer and scenic artist

Edward G.Rogers. Rogers was enlisted as early as 1911 to devise and develop visual effects methods for producer Charles Urban. In addition to glass work, Rogers also developed an early colour process known as

Kinemacolor.

Glass painting and special effects work in general really advanced a few years later under the great

Walter Percy Day (1878-1965) - generally acknowledged as the Grandfather of British trick photography - being responsible not only for it's application in British cinema but also for introducing the technique to the growing legion of French film makers on the other side of the English Channel. Day's film career began just after WWI in 1919 at Elstree in the UK, though just three years later he left for France as demand grew for his particular area of expertise, with Day already having had a proven track record in creating amazing visuals on glass. Day would produce a large number of superb, detailed glass shots - often elaborate and ornate ceilings, palace interiors and long defunct Parisian landmarks on scores of French films such as THE CHESS PLAYER (1927) and NAPOLEON (1927) with Day himself seen

in front of the camera in a few of the films in an acting capacity. Day returned to Britain in 1932. As I've previously written, Percy

(known to all and sundry as 'Poppa') would go on to have a long and highly respected career in photographic effects work, working non stop through to his retirement in 1952 and having trained many of Britain's foremost matte artists along the way.

Lastly, though by no means least, no article on glass shots or foreground painted cut outs could possibly be penned without paying tribute to a man I call

'The Maestro' - the late, great Spanish artisan

Emilio Ruiz del Rio (1923-2007). Emilio was a craftsman, it's as simple as that. His ability in solving cinematic problems with such elementary tools and tricks continue to enthrall this blogger. Ruiz mastered the art of merging artificial, wholly hand rendered foregrounds with live action - be it as traditional glass art, painted sheet metal cutouts, miniatures or folded two dimensional dioramas - all in camera as completely convincing scenes that would fool most everybody. Emilio started as assistant to scenic painter and effects man

Enrique Salva in 1942 whereby the duo worked together on backings, hanging miniatures and glass shots with Emilio quickly mastering all facets of trick work which would see Ruiz a highly in demand specialist in the field over the next 40 plus years, both in Europe and in Hollywood on a reported 450 films!

![]() |

| Artist Ferdinand Pinney Earle (foreground) at work in his studio on a matte for ROBIN HOOD (1922) while fellow painters toil away on additional shots. |

BACK IN THE EARLY DAYS...![]() |

| An atmospheric glass painted enhancement from the ground breaking German fantasy DIE NIBELUNGEN / SIEGFRIED (1924) |

![]() |

| From an old 1922 movie magazine which revealed all... |

![]() |

| The 'Hall Technique' at work at Germany's UFA studio for an early production of SCHEHERAZADE (1928) |

![]() |

| Classic glass shot set up from a time long, long ago... |

![]() |

| One of Norman Dawn's own detailed historic record cards. |

![]() |

| Schematic for what is thought to be the very first motion picture glass shot by Norman Dawn in 1905. |

![]() |

| MISSIONS OF CALIFORNIA - Dawn's own personal record. |

![]() |

| A portion of one of Norman Dawn's 800 odd trick shot cards where he meticulously detailed each step of the effects process as applied to each individual film he worked on. This one is HALE'S TOURS and gives an excellent indication of Dawn's visual sense and approach to making a glass shot. |

![]() |

| While I'm illustrating just a few of Dawn's fx shots in this blog, I'm just covering glass work and purposely not including his many composite matte shots and other tricks. Maybe another time... |

![]() |

| Another Dawn VFX card, this being from THE BLACK PIRATE (1911). Astonishingly, even the original 35mm nitrate clips survive (though some have decomposed). Not all of the 800+ cards however survive, with a good percentage lost. |

![]() |

| Detail of Dawn's oil painted preparatory sketch for the glass shot described above. |

![]() |

| The finished glass painting, sans live action. The unpainted bit of veranda will be lined up with actors on set. |

![]() |

| Dawn's most recognisable glass shot. I think it was called FOR THE TERM OF HIS NATURAL LIFE (1908) which apparently cost some outrageous sum to produce - some US$650'000 according to my information! That's a heap of dough for 1908 friends! |

![]() |

| Dawn's glass and camera set up in Tasmania where a roof and additional architecture was required to be 'replaced' via matte art. Apparently a fragment of this original glass painting still survives in the Australian national archive. |

![]() |

| The finished shot. |

![]() |

| THE DREAM (1912) |

![]() |

| Norman Dawn finished glass shot from THE DREAM, aka THE BROKEN COIN (1912) |

![]() |

| Norman Dawn glass shot from ORIENTAL LOVE (1916) |

![]() |

| A Dawn preparatory oil sketch for a glass shot of the ornate ceiling to be included in THE BEAST OF BERLIN (1917) |

![]() |

| Glass shot by Norman Dawn from THE LAST WARNING (1911) |

![]() |

| Glass shot on a sound stage from an unidentified film, circa late 1920's. |

![]() |

| This would appear to a glass shot. The film is D.W Griffith's massive INTOLERENCE (1916) |

![]() |

| While on D.W Griffith, here's another of his big epics - AMERICA (1924) - which had a cast of thousands too. Warren Newcombe painted the glass shots and I assume his associate Neil McGuire must have had a hand in them too. |

![]() |

| A clipping from a 1922 issue of Photoplay with an article entitled 'Does The Camera Lie?' (apparently, it does). |

![]() |

| Very rare glass shots from the silent version of THE PRISONER OF ZENDA (1922). Artist unknown. That castle may well be a foreground miniature by the way? |

![]() |

| Rare before and after Conrad Tritschler glass matte art from an unidentified early Cecil B.DeMille picture. |

![]() |

| Glass artist Paul Grimm is shown here putting the finishing touches on a location glass shot for the film WHERE THE NORTH BEGINS (1923) |

![]() |

| Some exquisite glass work from Allan Dwan's ROBIN HOOD (1922). Interestingly, although Ferdinand P. Earle is long associated with this film, his name isn't mentioned in the credits. Irving Martin, a pioneering Hollywood art director and matte painter gets his name up there, so maybe he did the shots? I love the top left shot of the ruins with the painted clouds drifting by on a separate glass. Stunningly poetic, and all the more so in this original toned restoration print. |

![]() |

| One of Ferdinand Pinney Earle's impressive in camera glass shot set extensions from ROBIN HOOD (1922). Long time Hollywood veteran Paul Eagler was special effects cinematographer. Paul would get an fx Oscar years later for PORTRAIT OF JENNIE in 1948 or so. |

![]() |

| Unidentified production with glass shot in progress, possibly Norman Dawn. |

![]() |

| Expansive glass painted set extension from the silent SCARAMOUCHE (1923) |

![]() |

| Some awesome Ralph Hammeras glass work from the old silent show THE LOST WORLD (1924) |

![]() |

| F.W Murnau's incredible SUNRISE (1927) is an experience all in itself, with dazzling visuals and then state of the art composite photography. This shot is, if I recall correctly, a multi part shot comprising live action, glass artwork and (I think) miniature trains. My memory aint what it used to be. |

![]() |

| Before and after matte from Paramount's THE SAINTED DEVIL (1924) made on the U.S East Coast. |

MEANWHILE IN ENGLAND AND FRANCE...![]() |

| Walter Percy Day on location in France filming a large glass painted effect for VERDUN (1928) |

![]() |

| Before and after illustration from a French film journal of one of Percy Day's glass shots in LES OPPRIMES (1922) |

![]() |

| A grand Percy Day glass shot from LA JOUEUR D'ECHECS / THE CHESS PLAYER (1926) |

![]() |

| Another bit of Day magic from LA JOUEUR D'ECHECS / THE CHESS PLAYER |

![]() |

| Percy Day glass shot from an unidentified French film, circa 1920's |

![]() |

| Another unidentified Day shot, possibly from the French version of THE THREE MUSKETEERS (1932). |

![]() |

| Before and after Day glass shot from Abel Gance's AUTOUR DE LA FIN DU MONDE (1930) |

![]() |

| LA TERRE PROMISE extensive and large sized glass shot. |

![]() |

| Unknown French film - Percy Day shot. |

![]() |

| A magnificently authentic trick shot from Abel Gance's huge epic NAPOLEON (1927). See below for a breakdown of this impressive visual effect. |

![]() |

| The limited set on a Parisian sound stage with Percy Day's superb (and vast) glass painted columns, walls, roof, windows and even beams of sunlight. |

![]() |

| Close up detail of Day's precise architectural draftsmanship. Pure bloody magic folks! |

![]() |

| The actual set prior to painted extension. Note just how spartan it actually is! |

![]() |

| Another NAPOLEON Day shot. |

GLASS PAINTED EFFECTS IN HOLLYWOOD DURING THE 1920's...![]() |

| Ferdinand Pinney Earle's camera crew set up a DANCER OF THE NILE glass shot on a Los Angeles location. Photo courtesy of Craig Barron's indispensible book The Invisible Art. |

![]() |

| Two Paul Detlefsen glass shots from DANCER OF THE NILE (1923) |

![]() |

| A beautifully rendered glass shot from RICHARD, THE LION HEARTED (1925) |

![]() |

| Lewis Milestone's ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT (1930) with a glass painted setting, possibly enhanced by the placement of a foreground miniature rooftop. Frank Booth was photographic effects supervisor. |

![]() |

| I'm not sure if this shot from KING OF KINGS (1927) is a glass shot or a composite matte shot. Howard Anderson snr handled the effects work. His son Darryl was a matte artist but I don't know if he was active this far back? |

![]() |

| One of many Paul Grimm glass shots from NOAH'S ARK (1929). Ellis 'Bud' Thackery was matte cameraman. |

![]() |

| The glass set up. Note, this photograph was taken off centre and not on the same axis as the motion picture camera whereby both the painted glass and the background set will match up perfectly. |

![]() |

| Another of Paul Grimm's NOAH'S ARK shots. |

![]() |

| Period London, as painted for the old 1922 version of LORNA DOONE |

![]() |

| Partial set on a stage before glass painting has been applied, from the old 1922 version of LORNA DOONE. Clipping from an ancient Photoplay magazine. |

![]() |

| Final glass shot as it appears on screen in LORNA DOONE. Frame taken directly from a restored, tinted 35mm print. |

THE THIRTIES AND BEYOND - THE ERA OF SOUND AND COLOUR...![]() |

| Two Jan Domela shots from Ernst Lubitsch's beautiful BROKEN LULLABY (1931) |

![]() |

| Frank Booth supervised the trick work at Universal for DRACULA (1930) among others. I'm inclined to think that Conrad Tritschler may well have painted these gothic shots. |

![]() |

| Conrad Tritschler did in fact supply these moody glass shots for the excellent WHITE ZOMBIE (1932) |

![]() |

| WHITE ZOMBIE - Conrad Tritschler shot. |

![]() |

| Also from WHITE ZOMBIE |

![]() |

| Another key exponent of both matte art and glass painting was Mario Larrinaga who is shown here sandwiched between two layers of one of his many 'stacked glass' set ups on the original KING KONG (1933) |

![]() |

| A very rare original 35mm test of the famous Skull Island glass shot from KING KONG. The final release prints are more closely cropped and don't show as much detail on the sides. Mario Larrinaga and Byron Crabbe were principal glass artists on the film, with other notable matte painters assisting such as Albert Maxwell Simpson, Henry Hellinick and Juan Larrinaga. |

![]() |

| Detail from a BluRay frame grab |

![]() |

| Skull Island as seen in the unfortunate sequel, SON OF KONG (1933). As poor as the film is, I prefer this glass shot of the island over that seen in the first film. Beautiful brushwork and density of mood here. The sharp crispness of the foreground painted element is a rarity in matte work and is a treat for researcher / fans such as myself. |

![]() |

| A test frame with glass painted jungle. There ain't no jungle like a Merian C.Cooper jungle as far as I'm concerned. I rewatched the DeLaurentiis KONG the other night and one of it's biggest failings (it has many) is the absolutely atrocious production design for Skull Island where it barely resembles your friendly local Mom and Pop garden nursery to me. At least Peter Jackson produced a fetid, frightening Skull Island habitat. |

![]() |

| KONG '33 Skull Island once again. I understand that many of the jungle shots were made as foreground glass shots while some were actual composite matte shots. |

![]() |

| Another rare shot that I came by, purported to be from that infamous, long lost spider pit sequence, though whether it actually is, I can't be sure. Left frame is the foreground glass prior to filming with stage set. |

![]() |

| KONG's famous log chasm glass shot (possibly multi layered?) |

![]() |

| A terrific pic of KONG's key matte artists and production illustrators Mario Larrinaga (left) and Byron Crabbe (right) sharing a joke while working on a glass painting. |

![]() |

| The strangely enchanting Fox film CHANDU THE MAGICIAN (1932) had some pretty ambitious effects shots in it and this shot which looks to me like a glass shot. Fred Sersen was on the effects. |

![]() |

| Although I don't have any frames, only this magnificent matte preparatory painting, Mario Larrinaga apparently did some great shots for Maurice Tourneur's THE ISLE OF LOST SHIPS, made in the late twenties, where he depicted a mythical island - a graveyard of many wrecked vessels. The shot was entirely painted on glass and in some scenes two painted glasses were used, with the first being stationary and painted to represent the island and it's piled up junk. The second glass was painted to represent the sea with a number of half wrecked hulks floating semi submerged. This glass was moved slowly across in front of the camera, giving the illusion of the ships drifting slowly with the tide. |

![]() |

| A Byron Crabbe glass shot from THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME (1932) where the sky and headland have been added. Two scraped off points on the horizon have will simulate buoy lights at night. |

![]() |

| No, it's not KONG, it's THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME which was filmed back to back with the monkey flick on the same sets and with some of the same actors and technicians. Still a fantastic painted scene no matter which film you see it used in. |

![]() |

| Glass shot artist Byron Crabbe shown here painting a foreground glass for THE LAST DAYS OF POMPEII (1935). Incidentally, the shot never got used and isn't in the final film sadly and really should have been. |

![]() |

| I've always tended to see this shot from the old Clark Gable MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY (1935) as probably being a glass shot rather than a composite matte shot due to the slight difference in sharpness whereby the painted area is surprisingly sharp against the somewhat softer live action portion. |

![]() |

| Warner's A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM (1935) was an eye popping experience visually - beautifully photographed and with some outstanding photographic effects set pieces. Byron Haskin, Fred Jackman and Hans Koenekamp provided the really very impressive visual effects. Paul Detlefsen was likely involved with the numerous glass shots. |

![]() |

| A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM |

![]() |

| The fairies materialise in A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM (1935) |

![]() |

| Spanish matte artist Alfonso de Lucas at work on EL HIJO DE LA NOCHE (1949). |

![]() |

| A poor quality frame from an unexceptional film, BAD LORD BYRON (1949) where Albert Whitlock has painted in a period ballroom. |

![]() |

| Korda's big Technicolor picture JUNGLE BOOK (1942) was loaded with effects shots. Effects boss Lawrence Butler utilised matte art, models and elaborate hanging miniatures to maximum effect. Fitch Fulton was matte artist and painted many shots. The three I've included here look to me as if they could be foreground glass shots, partly due to the contrivance of practical vines and foliage that appear in the immediate foreground and pass across into the painted area thus negating any matte line. Some studios like Fox would routinely bipack in actual tree branches and leaves gently swaying very successfully over static matte shots to give them life as seen in a ton of films. |

![]() |

| Another Fitch Fulton shot |

![]() |

| JUNGLE BOOK was a nominee (one of many) for best visual effects in 1942. Fact! |

![]() |

| Powell & Pressburger's stunning THE RED SHOES (1948) was a sheer delight and really one of kind. Many beautiful photographic effects sequences such as this beauty which has a nice dolly move following Moira Shearer against a seemingly vast glass painted setting. While many sources claim that Percy Day did the matte work, this is incorrect. Matte artists were Joseph Natanson, Ivor Beddoes and Les Bowie. George Gunn was optical process cinematographer. |

![]() |

| Clearly an on set foreground glass shot as the dancer's heads occasionally become superimposed behind the painted scenery. |

![]() |

| One of the greats of special photographic effects was Jack Cosgrove who is shown here preparing a painted glass for filming. Cosgrove was a master artist who understood just how much - or how little - was needed to be painted to sell a shot. Jack did wonders while working with David Selznick where he produced huge numbers of mattes and glass shots for films as diverse as THE PRISONER OF ZENDA, GONE WITH THE WIND and DUEL IN THE SUN to name but a few. Cosgrove was a legend with something of a wild side, and was reputed to have been incredibly sloppy at the easel, with cigarette ash and what have you dropping onto the matte painting and getting stuck in the wet paint. Often Jack was even drunk while rendering a matte shot, though as all who worked for or with him have testified, his work up on screen was sensational and looked a million dollars. Jack Cosgrove knew the business inside and out and was one of the best. |

![]() |

| Selznick's A STAR IS BORN (1937) had several matte shots by Jack Cosgrove as well as this interesting foreground glass shot at the end. A painted sky and setting sun was rendered on glass by Cosgrove and this was set up on the beach location for the sequence where Fredric March walks into the sea and commits suicide. A glass shot was required so that the camera could follow March down the beach and tilt up to gradually reveal the sky. Worked well. |

![]() |

| MGM's 1952 remake of THE PRISONER OF ZENDA opened with this very wide pan across a pseudo European alpine setting following star Stewart Granger and friend. I'm fairly confident that this is most likely a large foreground glass painting as the shot doesn't have that 'mechanical' optical printer move look to it had it been assembled optically. Plus, the grain and resolution look first generation to me. Warren Newcombe was head of the matte department. |

![]() |

| A close up look at the above fx shot. |

FOX RAISES THE GLASS SHOT BENCHMARK...

I've forever been impressed with the skills of the members of the 20th Century Fox special effects department where

anything and

everything seemed possible. In keeping with the theme of today's article, if there were just one studio that deserved singling out for ingenuity in the field of glass shots it would

have to be Fox. The Sersen department were masters at ustilising elaborate dual or triple panel painted glasses for spectacularly broad pans and fluid camera dolly shots to astonishing on screen effect. I have collected quite a quantity of these shots which are illustrated below.

![]() |

| 20th Century Fox's Sersen matte department, circa 1941, with much activity afoot. |

![]() |

| Fox's effects chiefs: Fred Sersen on the right and assistant (and successor) Ray Kellogg at left. Together they would design and oversee thousands of outstanding special effects shots over the years. Both Fred and Ray were experienced matte artists though they could turn their hand to all manner of trick work as the need arose. |

![]() |

| Ralph Hammeras (right) - senior multi-talented Fox effects man. |

![]() |

| On the Fox lot Fred Sersen (centre) supervises what appears to be a very complex multi-glass matte shot with as many as three large panels. Not sure what the film is but may be THE SECRET OF CONVICT LAKE (see further down this article) though it's hard to pinpoint. |

![]() |

| Raoul Walsh's excellent western THE BIG TRAIL (1930) was the first (or one of the first) widescreen films ever made, shot in the then untried 65mm with a process called 'Grandeur'. It's a sensational film in my book and has a ton of great matte shots throughout. Some seem to be composite mattes, though I'm guessing some might be glass shots due to rock steady, crisp merging of painted and real. Fred Sersen was credited for the 'Art Effects' and his work is superb. |

![]() |

| Also from THE BIG TRAIL, I'm fairly sure this is a glass shot as a soft blend can be seen on both tree trunks where painted meets actual - but I might be wrong? |

![]() |

| Among Fox's developments were in the field of making dull skies more dramatic by way of foreground art or, as in this case, special photographic transparencies where the lower portion of the transparency was clear, thus allowing a perfect bleed through into the actual physical setting. Charles G. Clarke developed the technique and I think won a special technical Oscar for same. So many Fox films had fantastic skies - HOW GREEN WAS MY VALLEY, MY DARLING CLEMENTINE, JANE EYRE and more. |

![]() |

| Poor quality illustration, but I'm sure you get the message. |

![]() |

| Glass shot from the Fox comedy GIRL'S DORMITORY (1936) |

![]() |

| Another from the same film. |

![]() |

| Schematic of 20th Century Fox's dual plate glass set up as used on many productions, as shown below... |

![]() |

| A frame from part of the long camera pan across multiple painted glasses from the excellent Gregory Peck film KEYS TO THE KINGDOM (1944). Note the mismatched division between painted and genuine on the tree trunk. |

![]() |

| Sequential frames from the aforementioned amazing trick shot. Incredible! |

![]() |

| Same sequence |

![]() |

| Tilt up glass shot from the Fritz Lang(!) cowboy picture WESTERN UNION (1941) |

![]() |

| A frame from a pan across painted extensions from the film CLIVE OF INDIA (1935) |

![]() |

| Ralph Hammeras and Fred Sersen engineered a terrific ride through hell in the not very good and downright unfathomable DANTE'S INFERNO (1935). Miniatures, glass art and optical combinations in an arresting sequence. |

![]() |

| Even the timeless family friendly classic HEIDI (1937) had a dynamite opening effects shot where the camera follows our protagonist all the way from this picturesque Alpine valley around and into the town square. Multiple glass paintings strategically placed (and concealed) work a treat. See below... |

![]() |

| Frames from the tour de force opener mentioned above. Note the tree and religious sign pole which are purposely placed to hide the point where the large wooden framed glasses are set up. Fred Sersen, Ray Kellogg and Ralph Hammeras really knew how to use this technique to the best effect. |

![]() |

| Final frame in the above pan. |

![]() |

| Another elaborate glass pan shot from Fox, this time from THE RAZOR'S EDGE (1946) where the camera travels from a moody evening sky, down across a body of water and along past some painted trees to a character standing by a window. |

![]() |

| A slight pan across an exterior with a painted glass top up from REBECCA OF SUNNYBROOK FARM (1938) |

![]() |

| Another from the same film. |

![]() |

| The final scene from THE SECRET OF CONVICT LAKE (1951) with the ever present Fox tree trunk to conceal the trick. |

![]() |

| Same film |

![]() |

| Now, this one's a beauty. The opening shot from the Richard Burton thriller MY COUSIN RACHEL (1952) |

![]() |

| A close look at the painted - live action blend, which is invisible. |

![]() |

| Fox just loved to close their shows with either a great matte or one of these uniquely attention grabbing pan glass shots. This one from THE SNAKE PIT (1948)... and you guessed it... there's that tree again! |

![]() |

| Close up of the final frame. The Nodal Head camera mount was really essential to pull off this sort of pan. |

![]() |

| A long dolly shot across multiple painted glasses for the Civil War film TWO FLAGS WEST (1950) |

![]() |

| Frame from the TWO FLAGS WEST dolly glass shot |

![]() |

| Sersen Department matte artist Christian von Scheidau at work on a large dual panel glass shot for STATE FAIR (1945) which will serve as a wide panning establishing shot. |

![]() |

| Chris von Scheidau's finished painting merged in camera with the car park live action. |

![]() |

| One of the frames from that STATE FAIR glass shot pan across. |

![]() |

| DAVID AND BATHSHEBA (1951) glass shot... and there's that ubiquitous Fox prop tree there again. Works though. |

![]() |

| Same film. Can you see the blend? |

![]() |

| Matthew Yuricich mentioned in his oral history which I published in 2012 that he painted one of THE ROBE (1954) mattes as an on location glass shot. He said it was one where someone riding a donkey approaches a city. This is the nearest scene I could find in the film to what Matthew described, though I'm not sure if it's the one. |

![]() |

| The huge, overblown Elizabeth Taylor epic CLEOPATRA (1963) was, to me, always something of a yawnfest - Oscar winning matte effects notwithstanding. There were only a couple of mattes in the film though they were very impressive. I believe longtime Fox all round effects man Ralph Hammeras painted this substantial two-panel glass shot. The division between the two glasses is concealed behind that statue in mid frame. |

![]() |

| BluRay close up of Hammeras' glass painted landscape, city and fleet of ships. |

![]() |

| Diagram from a VFX book |

![]() |

| Now folks, this CLEOPATRA shot is a bona fide winner. An altogether realistic pan across the port of Alexandria with distant landscape and city painted on two massive panes of glass by Polish born though Rome based matte painter Joseph Natanson, assisted by British landscape artist Mary Bone. In his memoir, Natanson wrote of his experiences working on this massive shot and how significant alterations had to be made to it after a seasonal change of weather revealed quite a different actual Roman landscape behind the painting than expected, due to low fog at the time of painting. Joseph recalled how the film's director Joe Mankiewicz brought stars Taylor and Burton up the scaffold to see how he planned to present historic Alexandria on screen - to their amazement. |

![]() |

| Close view of part of the shot. Note, the foreground's large columned buildings were actually constructed on location in Rome, with just the far away cityscape etc being Natanson artwork. The statue at right is the demarcation point between the two glasses. No tree this time! As good as this work is, I'm still surprised that CLEOPATRA took home the VFX Oscar and denied Hitchcock's THE BIRDS that honour. |

![]() |

| Same shot. Later in this same blog article you will see a very rare out take of a completely different CLEOPATRA glass shot made in England at Pinewood I believe while the production was still based in the UK before Fox pulled the pin on it and eventually scrapped the shoot and moved it all to Italy. |

![]() |

| Now, this one's a curiosity. The WWII action film BETWEEN HEAVEN AND HELL (1956) had this intriguing bit of matte work that I think must be an outdoor glass painted shot. Reason being that the actor stands up and as evidenced in this frame, his head doesn't get cut off by the matte line, rather it becomes translucent with the painted village briefly showing through it. Ray Kellogg was effects supervisor and Emil Kosa jr was in charge of matte art. |

![]() |

| It may well be a standard composite matte shot but the extreme razor like sharpness of the small town against the rest of the overall rather soft CinemaScope frame is suspicious. Two totally unrelated focal points on one apparent plane. The film is RIVER OF NO RETURN (1954) |

![]() |

| One of the most famous cinematic leaps of faith in movie history, BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID (1969). See below for details... |

![]() |

| Under effects supervisor L.B Abbott's direction, a large photo blow up of rock wall formations was hand retouched by the matte artist and glued to a large, vertically mounted sheet of glass on location at Fox's Malibu Ranch. |

![]() |

| The glass shot set up. Bill Abbott would line up the camera to facilitate a quick tilt down, following the action as two stuntmen jumped off a purpose built tower, into the lake. The glass shot concealed the metal tower. |

![]() |

| The matte artist touches up the photo/artwork in readiness for the shot. Fox's longtime matte artist Emil Kosa jr died the year before so probably this is another artist. |

THE MAESTRO - EMILIO RUIZ DEL RIO...![]() |

| One of my all time favourite special effects exponents would be the late Emilio Ruiz, who is shown here with one of his incredible foreground painted cutouts - a specialty he mastered to the highest degree over his very long 45 year movie career. |

![]() |

| Recently, my friend in Spain, Domingo Lizcano, who knew and had worked with Ruiz, has published a comprehensive book on Spanish special effects titled; Effectos Especiales En El Cine Espanol, from which this photo came. Most of what I know about Emilio has come to me over the years from Domingo who is also a fountain of knowledge on all aspects of European trick photography. |

![]() |

| Emilio painting a major set extension while on location for LEGIONS OF THE NILE (1959) |

![]() |

| The final glass shot composite. |

![]() |

| 2nd Unit Cameraman, John Cabrera on location for CONAN THE BARBARIAN (1982) posing with one of Emilio's undetectable foreground paintings, rendered on thin sheet of aluminium which was then cut out carefully and mounted on a hidden pole. |

![]() |

| Ruiz painting another CONAN foreground shot, though I don't recall it being in the film. |

![]() |

| For CONAN's final scene, Emilio was tasked with painting in a distant valley and landscape on glass. Although filmed, director John Milius made a choice to do it differently and handed the footage over to effects man Jim Danforth to paint in an entirely new valley. That's the movie biz I guess. |

![]() |

| Emilio at work on one of his 450 or so film assignments. When I quizzed a friend in Madrid who has worked with and interviewed Ruiz, just what ever happened to all of these wonderful old masterpieces of matte art, he told me that the pieces were usually just thrown away in the garbage once they had fulfilled their need....simple as that. So sad! |

![]() |

| Another of Emilio's elaborate painted cut outs all set for a scene in SEA DEVILS |

![]() |

| ...and as it appears on screen. |

![]() |

| A terrific behind the scenes view of a major effects shot for the Spanish film OFICIO DESCRUBIDOR (1982) |

![]() |

| Working here on a sizable painting of New York city for the film LUZ DE DOMINGO (2007). This was one of the very last mattes made by Emilio. |

![]() |

| The painting of NYC, not yet in position for filming. Note the extraordinary detail. |

![]() |

| And there you have it...a photo real trick shot in LUZ DE DOMINGO (2007) |

![]() |

| Ruiz at work on a matte painting of Notre Dame in collaboration with frequent director and friend Enzo G. Castellari |

![]() |

| Ruiz with his assistant pose with an impressive fortress foreground matte painting for an unknown film. When asked why he chose to paint his in camera mattes on metal, Ruiz replied that back in 1955 he had painted an elaborate cityscape on glass for a film, and the glass broke accidentally. It was then redone on wood which was then cut out to conform precisely to that of the artwork. From that point on alternatives such as metal or aluminium were chosen and used as often as possible. |

![]() |

| The fortress matte painted cutout as seen in the final (unknown) film. Stunning in it's simplicity. |

![]() |

| One of the production crew helps to set up an Emilio Ruiz glass painting for a shot in the abysmal RED SONYA (1985). |

![]() |

| The entire castle is a cut out matte painting rendered on aluminium for the film DEVILS POSSESSED (1974) |

![]() |

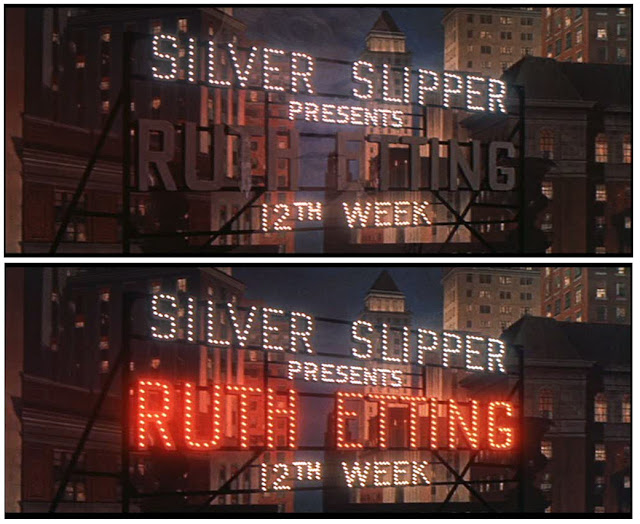

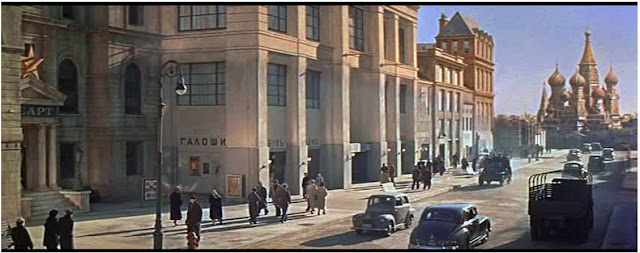

| Ruiz made his own spectacular vista of ancient Rome for the comedy S.P.Q.R: 2000 AND A HALF YEARS AGO (1995). The top left picture shows the actual location (maybe Rome or Madrid?). Top right we can appreciate Emilio's superb draftsmanship in the detailed pencil drawing from which the matte painting will be rendered. The lower left image shows the matte art partially positioned, though not camera ready yet as the modern streets and traffic can still be seen. Lower right has Emilio posing with his wonderful matte art that is now perfectly positioned, concealing the modern trappings below, but allowing specific actual landmarks to be still visible in order that live action may be staged. |

![]() |

| Close detail look at the final matte art (I'm not sure what support Ruiz has painted it onto?). From this angle the edge of the superb art is not yet properly aligned. Magnificent. |

![]() |

| Before and after set up shots for a foreground matte painting for SCHEHEREZADE (1962) |

![]() |

| Out take from the final shot. |

![]() |

| Emilio at work on a shot for the Spanish film LA NINA DE TUS OJOS (1998). See below... |

![]() |

| Step by step matte construction for LA NINA DE TUS OJOS |

![]() |

| Final in camera composite. |

![]() |

| One of my all time favourite behind the scenes trick shot photographs is this one with Ruiz posing with his amazingly convincing painted cutout of the World War 2 airfield for the relatively minor film DIRTY HEROES (1967) |

![]() |

| DIRTY HEROES - final shot. |

![]() |

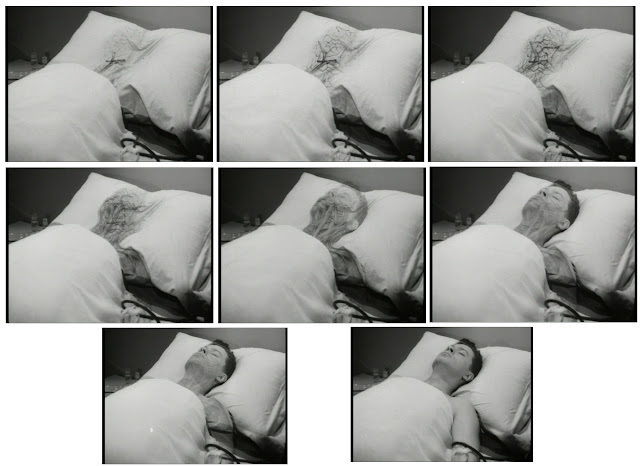

| Not long before his passing, Emilio participated in the making of a special feature length documentary detailing his career EL ULTIMO TRUCO (2008) in which he took the audience step by step through the stages of the making of a major matte painted glass shot which integrated elaborate miniature action and live performers. |

![]() |

| While helpers set up a miniature scale bridge (complete with mobile model tanks), that seemingly bridged two canyon walls, Emilio painted on glass the actual canyon, a valley beyond the bridge and stone bridge piles supporting the distant miniature bridge. |

![]() |

| The master at work... |

![]() |

| Miniature tanks and toy soldiers on a belt driven, bandsaw gimmick. |

![]() |

| The finished on screen effects shot, all done in camera in one take. Partial miniature bridge, model tanks, toy soldiers marching, painted valley, cliffs and scenery. A friend of mine who authored the recent book on Spanish effects work is on the motorcycle in the foreground. Great stuff! |

![]() |

| Unique before and after glass shot by Emilio Ruiz for the film CANTABROS. Note the left image where the painted encampment has been photographed from a different angle than that of the motion picture camera, whereby the rows of tents all seem to be curiously floating in space. At right, we see the invisible final trick. |

![]() |

| Ruiz was kept very busy by director Enzo Castallari on the film THE INGLORIOUS BASTARDS (1978) with all manner of glass shots, painted cutouts and cleverly devised miniatures. This shot comprises an actual, staged live action foreground of a dozen or so wrecked vehicles with everything else beyond the halfway point of the frame being an exacting painted cutout with scores more bombed military vehicles, the mountain and the entire town atop. |

![]() |

| The trick revealed! |

![]() |

| One of my all time favourite Ray Harryhausen films, and one sorely underappreciated, THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD (1974) was a winner all the way for me (* see my special blog post on it). This shot is one of those scenes one just assumes to be an actual location, though it's largely an Emilio Ruiz trick shot. |

![]() |

| How it was done. The ship was a full size set, while all of the scenery, docks and city were matte art painted on aluminium, cut out and carefully aligned with the set. |

![]() |

| Detail from the above matte art. |

![]() |

| GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD - foreground matte set up. |

![]() |

| Another GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD foreground matte. The shot looks sensational, especially with the very natural, fluid camera pan which follows the horse and rider toward the city. Utterly convincing. |

![]() |

| Emilio with his walled city matte art, painted on aluminium sheeting and mounted outside of camera range. |

![]() |

| From the same film, Emilio has flawlessly added in the entire Forbidden City as a foreground painted cut out. |

![]() |

| Ruiz painted this entire town, with just a few gaps for extras and action to be visible, for the excellent Stacy Keach film DOC (1971) |

![]() |

| Foreground trick shot revealed - from CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS: THE DISCOVERY (1992) |

![]() |

| Glass shot setup for a harbour filled with warships from the Enzo Castellari film EAGLES OVER LONDON (1969) |

![]() |

| An airfield lined with fighters is mostly a Ruiz foreground painting. The shot is a wide pan following pilots as they rush out to their planes. Film is EAGLES OVER LONDON. |

![]() |

| Another frame closer up. |

![]() |

| Emilio with an enormous glass set up for a LEGIONS OF THE NILE (1959) matte in what would appear to be a double glass panning shot. |

![]() |

| Another elaborate foreground painted set up for THE LOVES AND TIMES OF SCARAMOUCHE (1976) with the result being completely believable and a significant budget saver. |

![]() |

| Ruiz paints a dark and brooding sky and horizon on glass for THE FRENCH REVOLUTION (1990) |

![]() |

| For the historic adventure TAI PAN (1986), Ruiz created a number of impressive vistas of villages, towns and ships at sea - some with painted cut outs and others with forced perspective miniatures. |

![]() |

| Numerous sailing ships anchored were in fact completely glass painted trick shots, with even the islands and headland being part of the gag. Movie is TAI PAN (with a fatally miscast Bryan Brown in cheesy Oriental make up if I recall!) |

![]() |

| TAI PAN |

![]() |

| Now, I'm not sure if this is one of Emilio's shots, but sure has all of his hallmarks. A foreground painting of the entire town, either on glass or as an aluminium based cutout from the Lee Van Cleef western BAD MAN'S RIVER (1971) |

OTHER GLASS SHOTS - DISNEY, DANFORTH, BAVA, BOWIE, TOOK & STAMFEST![]() |

| This frame, from Rank's THE PLANTER'S WIFE (aka OUTPOST IN MALAYA) from 1952 is an interesting combination of a painted backing, a Bill Warrington miniature, complemented with an Albert Whitlock glass painting where much of the trees and foliage has been added in on glass. This sort of thing was quite common where depth of field could sometimes be better maintained by painting foreground scenery on a single plane of glass rather than having a long miniature set where focal points might be problematic. Whitlock's fellow matte artist at Rank, Peter Melrose discussed this in an interview where he mentioned it was common to sometimes paint up to 4 or 5 individual glasses and arrange them in layers for shots such as this. Of course Larrinaga and Crabbe did alot of that back in 1933 on KONG's miniature sets to breathtaking effect. |

![]() |

| One of those mattes that nobody ever spots, from THE INN OF THE SIXTH HAPPINESS (1958) where a Chinese village has been painted in on glass for the narrative as well as to conceal large looming hydro-electric plant, as detailed below. |

![]() |

| Very insightful breakdown that, had it not have been for this article I'd never have been aware of. No idea as to who painted this, nor the other rather nice matte shots. |

![]() |

| From Raymond Fielding's still excellent textbook The Technique of Special Effects Cinematography which I bought in the mid 1970's and still peruse it to this very day. |

![]() |

| From the films FLAME IN THE WIND and AUTO DE FE - both made in the 1960's at an American University. |

![]() |

| One of Ralph Hammeras' glass paintings from the somewhat better than it sounds THE BLACK SCORPION (1957) |

![]() |

| Peter Ellenshaw paints the magnificent San Francisco port on glass while Ub Iwerks looks on for 20'000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA (1954) |

![]() |

| Another of Ellenshaw's on location glass shot set ups, this being from Disney's THE GREAT LOCOMOTIVE CHASE (1956) |

![]() |

| Also from that same film with the town painted on glass. The glass method does seem a little ponderous and labour intensive at times. I'm not sure, but that may be Albert Whitlock standing facing us in that b&w photo as he also painted shots on this film under Peter. |

![]() |

| For Disney's SWISS FAMILY ROBINSON (1959) Peter once again painted glass shots directly on location in Jamaica. |

![]() |

| SWISS FAMILY ROBINSON - now which is the real Junk and which one is Peter's painted Junk? |

![]() |

| Another Ellenshaw glass set up, this time for KIDNAPPED (1960) |

![]() |

| Peter Ellenshaw's evocative ice cavern glass painting on the stage at Pinewood, England for an in camera live action pan from IN SEARCH OF THE CASTAWAYS (1962) |

![]() |

| As seen in the final film... |

![]() |

| Italian director and all round film technician, Mario Bava was also known to devise and even paint his own glass shots for his and other director's films, such as Dario Argento (more on that later). This is from the Italian film NERO'S MISTRESS from the 1960's. |

![]() |

| Another glass shot, most likely done by Bava himself, from the film I, VAMPIRI (1962) |

![]() |

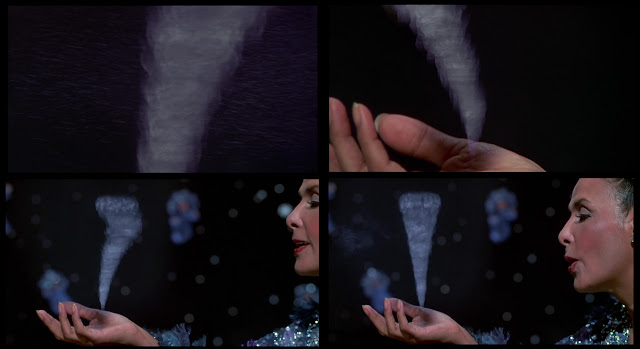

| In the 1960's, Italian cinema made a specialty out of various pulp comic book styled super hero/crime fighter genre pieces, with Mario Bava's DANGER DIABOLIK (1968) being the best of the bunch by a long shot. Incredible style, decadent design, an Ennio Morricone score that I still listen to now, the so damned cool John Philip Law .... and of course the delectable Marisa Mell. The film is a treat, with the numerous visual effects just adding to the fun. This scene in the underground lair is an eye opener (pic below) with an amazing, extra wide pan across from one piece of live action to another on the other side. |

![]() |

| Bava's camera lined up on what appears to be a giant glass painting (though some of the shot may be model work), with clear spaces left unpainted for Law and Mell to enter the grooviest of bachelor pads this side of an Austin Powers flick. |

![]() |

| More matte and glass work from DANGER DIABOLIK. The top left comprises of a glass painted element according to the DVD audio commentary, with the castle shots also being glass shots. They don't make 'em like this any more. |

![]() |

| Spanish effects man Julian Martin with his matte painted cut out in position for THERESA DE JESUS |

![]() |

| Another painted foreground matte by Julian Martin, this time for the Spanish film LA HORA DE LOS VALIENTES. |

![]() |

| Regarded by many as John Huston's worst ever film, THE BIBLE-IN THE BEGINNING (1966) had a couple of, until now, uncredited matte effects shots. My good friend in the Spanish film industry informed me just recently that this wonderful on location glass painted shot was the work of Italian artist Silio Romagnoli. Incidentally, noted film critic Leonard Maltin said that ..."this is one film where you are better off by reading the book instead!" |

![]() |

| A glass painted city by Spanish artist Julio Esteban from the film CUANDO ALMANZOR PERDIO EL TAMBOR (1984) |

![]() |

| German cinema somehow found the time and resources between invading neighbouring countries and causing mass mayhem on an epic scale, to produce this colourful fantasy in 1943, MUNCHAUSEN - a film that decades later one Terry Gilliam would also tackle, though as with all of Gilliam's films it's very much an acquired taste. |

![]() |

| For Dario Argento's under rated chiller INFERNO (1979), Mario Bava was on hand to provide some foreground glass shots of the non existent creepy as hell witches coven apartment building smack bang in the centre of a non existing New York city. One of Argento's best films, especially when compared to the absolute shit he's been making in the past ten or 15 years. Time to retire to the vineyard Dario. |

![]() |

| Not sure if this is a glass shot or a regular matte but I'll include it anyway. The John Wayne adventure WAKE OF THE RED WITCH (1949) had a number of interesting mattes in it. |

![]() |

| Another WAKE OF THE RED WITCH shot. I don't know who did them but old time pioneer Lewis J. Physioc had a long association with Republic pictures when it came to matte work. |

![]() |

| Location in Portugal (I think) where Spanish effects man Gonzalo Gonzalo (no, that's not a typo) has painted and set up an in camera cut out shot of a Portugese castle and fortress which will cover over the existing modernised town of the incorrect historic period for LA VIDA LACTEA (1992) |

![]() |

| I'm pretty certain that this shot is a glass shot, as seen in the laughably bad STARCRASH (1979) - aka THE ADVENTURES OF STELLA STAR. Oh Lordy, what on earth were they thinking? |

![]() |

| I grew up as a teen watching the hilarious Tim Brooke-Taylor, Graeme Garden & Bill Oddie BBC comedy THE GOODIES from the early 1970's, in which so much amazing old style camera trickery was employed week after week - all harking back to Chaplin, Lloyd, Turpin and Sennett. From stop motion actors(!), brilliantly edited jump cuts of actor to dummy destruction (so bloody funny) and much undercranking of the 16mm camera - not to mention the occasional matte shot and blue screen comp. A completely unique, one of a kind experience that still gets a giggle out of me. Anyway, this set up is one of the low budget glass shots used in an episode where the Roman Forum had to be created on a footy pitch just outside London. Kudos to the highly creative BBC special effects department for constantly coming up with so many great physical and visual slapstick gags - for which I'm willing to forgive them for the awful fx work that cropped up week after week on DR WHO (which I also grew up with). |

![]() |

| A glass painted top half of a set from a Spanish production who's title I can't recall. The white line is a deliberate marker to indicate the join. |

![]() |

| Glass painting has been widely used in Eastern European cinema as well. Czech matte artist Jiri Stamfest created this scene for a Czech TV version of SNOW WHITE (1992) |

![]() |

| A still photo with the glass artwork in alignment with the set. |

![]() |

| Another of Jiri Stamfest's wonderful glass shots, this from THE WITCHES CAVE (1989) |

![]() |

| Jiri Stamfest glass painting for NEXUS (1994) before being precisely lined up with the location set. |

![]() |

| Jiri's own still photograph taken with the frame and supports visible, though showing the correct line up. |

![]() |

| A Les Bowie glass shot from THE LEGEND OF THE 7 GOLDEN VAMPIRES (1974) - a rollicking hybrid of Kung Fu and Hammer horror, though this shot never really worked, especially on the big CinemaScope screen back in the day. |

![]() |

| Les Bowie at work on a large glass shot. |

![]() |

| Another Les Bowie shot for Hammer. This time it's from THE TERROR OF THE TONGS (1961), and although I can't be certain, I seem to remember reading that it was a glass shot rather than a matte composite. |

![]() |

| The Skotak brothers, Dennis and Robert, have entertained us for decades with their ingenuity and no-nonsense effects work that has always impressed me. Here they are with a glass shot from the post apocalyptic show AFTERMATH (1979) |

![]() |

| Director James Cameron got his start in the business working with the Skotak brothers on visual effects for several films. Here is Jim touching up a large photographic cut out of Manhattan which would form a memorable and undetectable glass shot in John Carpenter's entertaining ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK (1981) |

![]() |

| Antonio Miguel painted this glass shot for the Spanish film ALFONSO XII (1959). Note, there is a slight disparity in focus between the live action and the glass painting. |

![]() |

| A good diagram of the methods for dual glass placement and use. |

![]() |

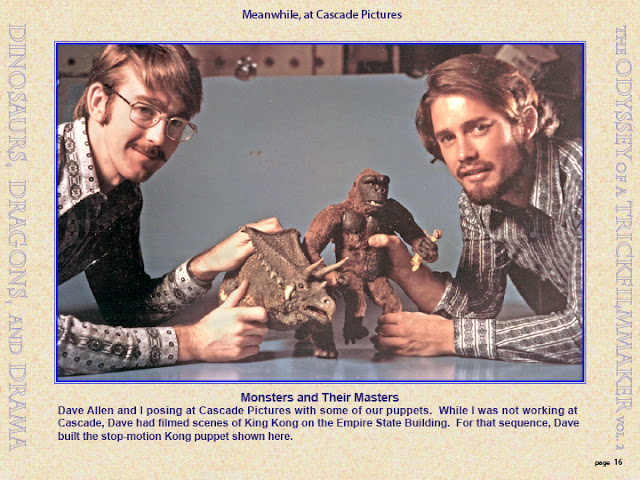

| Animator, cinematographer, matte artist and all round top rung effects guy Jim Danforth painted this experimental glass shot very early on in his long career. |

![]() |

| From Jim's book Dinosaurs, Dragons and Drama-Volume One, in which he extensively details his amazing career. |

![]() |

| British matte painter Humphrey Bangham paints a glass shot on location for THE NEW ADVENTURES OF PINOCCHIO |

![]() |

| The low budget sci-fi flick TRANCERS (1985) had this shot as an opener, which to me has always looked like a glass effect set up on a beach. Just how they concocted not one, but two sequels to this film amazes me! |

![]() |

| Les Bowie painted so many mattes over his long career, spanning more than 30 years from early times at Pinewood through to his untimely death in 1979. This location glass painted shot is from LANCELOT AND GUINEVERE (1963) also known as SWORD OF LANCELOT. |

![]() |

| UK matte artist Leigh Took is seen here painting one of many glass shots for the big miniseries THE LAST DAYS OF POMPEII from the late 1980's. |

![]() |

| At left is the massive tower specially constructed for Leigh to execute and Neil Culley to shoot the glass shot. At top right is a test with the mountain Vesuvias still be be corrected. |

![]() |

| On that same show, we can see photographic effects supervisor Cliff Culley lining up the camera as mounted on a special nodal head, for a tilt down glass shot. That's Cliff's son, Neil at left who was effects cameraman. |

![]() |

| At extreme left is matte artist Cliff Culley applying last minute finishing touches to the village and mountain artwork. |

![]() |

| The matte art still to be lined up. |

![]() |

| ...and the finished scene prior to 'action'. |

![]() |

| Leigh Took adding detail to one of his Pompeii glass shots. |

![]() |

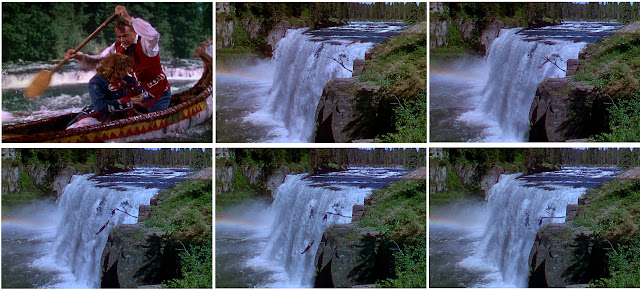

| The strange, erotic and sometimes downright baffling WIDE SARGASSO SEA (1993) had this painted shot which was screen credited as 'Boat Matte Composite by Howard A. Anderson'. Bruce Beresford's BLACK ROBE (1991) had a similar shot the year before which the director mentioned as being the old style glass shot. |

![]() |

| There were several mattes in MONTY PYTHON'S LIFE OF BRIAN (1979) with both Ray Caple and Bob Cuff on board painting shots. This is one of Caple's shots, and from what I recall from a staffer at Peerless Optical, Ray did this as an old style glass shot on location. |

![]() |

| As many times as I have seen John Boorman's visually stunning but oh so dense ZARDOZ (1974), I still have trouble with it... but keep going back for another try! Anyway, I'd never spotted this until the Associate Editor of Cinefex, the most affable Mr Joe Fordham told me about it and sent me the frame. Apparently it was done on location as an original glass shot. Oh, and there's no truth to the malicious rumour that Joe played the part of 'Brett' in Ridley Scott's ALIEN.... it was Harry Dean Stanton ;) ;) |

![]() |

| Low budget glass shot here from Brett Piper who knows a thing or two about making a film single handedly,with stop motion work being his specialty. This is a far more effective glass shot than Brett himself reckoned it to be in an email a while back. The show was A NYMPHOID BARBARIAN IN DINOSAUR HELL - which of course is not to be confused with the Howard Hawks film by the same name, nor the Francois Truffaut picture of similar title...nor the Woody Allen Broadway play of a not too dissimilar name. |

![]() |

| Now here's a fascinating one.... a Matthew Yuricich glass shot from the midget comedy UNDER THE RAINBOW (1981). If you like 'little people', then this is your film! |

![]() |

| Yes, it was an amusing film within a film gag, where Jack Krushkin, I think, reveals the gag to the audience during the shoot of some low rent GWTW extravaganza (saw this thing more than 30 years ago). |

![]() |

| Kind of neat and the highlight of the film. |

![]() |

| Matte artist Pony Horton originally got his start at Van Der Veer Photo Effects and would work on several low budget films such as this one WIZARDS OF THE LOST KINGDOM (1988) where some good glass work was carried out. |

![]() |

| The television series BLAKES 7 from the eighties was never one I took to, though here is a rare location glass shot from said series. I think it was a BBC affair. |

![]() |

| I mentioned earlier about the unused Pinewood effects footage from CLEOPATRA (1963) which was scrapped once the over priced production went into long term hiatus and eventually shifted it's cast to Rome and started afresh. These frames don't really compare with the wonderful Joseph Natanson glass shots that feature in the finished film, though are definitely worthy of inclusion here, for historic reference if not for any other reason. Although it was filmed at Pinewood I have seen documentation which states that Wally Veevers matte department over at Shepperton was engaged and in fact did shoot some mattes for it. Not sure why that was, as Cliff Culley was Pinewood's matte artist. |

![]() |

| UK based artist Ian Glassbrook painted this magnificent glass shot of Hampton Court for what I think may have been a television commercial. |

![]() |

| Glass painted matte work by Canadian artist Joy Hanser from the film THE LOVE CRIMES OF GILLIAN GUESS (1994) |

![]() |

| Albert Whitlock painted this glass shot which was filmed on a New York location for Sidney Lumet's THE WIZ (1978). The glass shot was required in order to have a fluid camera pan following the characters as they came into frame and danced up the bridge. This looks great here in HD BluRay. |

![]() |

| Doug Ferris and Wally Veevers provided some subtle matte art and opticals for John Boorman's staggeringly good EXCALIBUR (1981). A modestly budgeted British film that looked absolutely breathtaking up on the silver screen - exquisite lighting camerawork by Alex Thompson that should have received an Oscar - outstanding art direction and costume design too. This shot, and some others were, I'm told, done on location as glass shots. |

![]() |

| I don't know what the film is here, the site on the web I found it on years ago stated it was from SUPERMAN IV but I couldn't find any such shot in it. Harrison Ellenshaw was the fx boss on the show and he couldn't recognise it either. The mattes were all done in England for that film. Looks like a photo paste up of Central Park in NYC on glass to me. |

![]() |

| The many times remade THE PRINCE AND THE PAUPER had a new lease of life in this British version in 1977. The film was good and featured absolutely sensational optical work by Wally Veevers and Doug Ferris, with some of the finest and most creative 'twin' effects I've ever seen. Aside from the opticals the film had a few foreground glass paintings by Dennis Lowe and Doug Ferris which were set up and filmed on location in Hungary, doubling for, I think, Westminster Abbey in London(!) The glass shots were actually large blow up photographs, retouched and hand coloured by Dennis, who also told me some funny stories about dealing with Wally. |

![]() |

| Dennis Lowe foreground hanging painting of Westminster Abbey. Doug Ferris later did some fix up work on some aspects that displeased Veevers apparently. |

![]() |

| Another tilt down glass shot from THE PRINCE AND THE PAUPER (1977) |

![]() |

| A nice look here at a semi-professional glass shot set up with a 16mm Bolex. I think this image came to me from noted visual effects man David Stipes, himself a skilled matte painter and effects cameraman. |

![]() |

| The enthusiastic Don Dohler was as creative as he could be on his miniscule budget 16mm films such as THE ALIEN FACTOR and many more, with soon to be in demand effects guys like Ernest Farino getting his start in the fx industry before getting on board with top flight effects houses like Fantasy II. In this illustration artist Larry Schlechter paints an alien spacecraft here on glass for an un-named Don Dohler film |

![]() |

| David Lean's wonderful adaptation of E.M Forster's A PASSAGE TO INDIA (1984) was a visual treat. Several effects shots in the film, supervised by Robin Browne, with this shot being a favourite. From what I recall from discussions with Stephen Perry at Peerless Optical, this shot may have been a glass shot filmed on location. Stephen seemed to recall the artist as being a woman, but couldn't remember her name. |

![]() |

| I've always admired the work of matte artists Rocco Gioffre and Mark Sullivan, with this ingenious trick shot from the Madonna comedy WHO'S THAT GIRL (1987) being of particular interest. The shot involved a car (and it's driver) dangling from a building, several stories up... |

![]() |

| ...the entire building was an elaborate glass painting by Mark Sullivan and Rocco Gioffre with a carefully prescribed area scraped away that exactly conformed to the shape of the large scale miniature car, which was set up several feet behind the painting against a small painted wall. Below this model car was an articulated puppet of actor Griffin Dunne which was animated - struggling for his life - in stop motion fashion by Gioffre to excellent effect. |

![]() |

| A closer look at the foreground glass painting. |

![]() |

| Effects maestro Derek Meddings puts the finishing touches on a large glass painting by highly regarded UK scenic artist Brian Bishop for the 007 film GOLDENEYE (1995). The area left clear will be lined up with a miniature set whereby a jet aircraft will land. Note, I was told by someone in the UK business that this was painted by Bob Fisher, so I don't know for sure who did it. |

![]() |

| British matte artist Leigh Took at work on an outdoor glass shot for a UK television commercial. |

![]() |

| Long time UK matte artist, Ray Caple, is busy here painting a glass shot of ships at sea on location in Malta for the Michael Caine war picture PLAY DIRTY (1968) |

![]() |

| One of Ray Caple's glass shots from PLAY DIRTY |

![]() |

| Jean-Jacques Annaud's Medieval murder mystery, THE NAME OF THE ROSE (1986) managed to sneak in a couple of small mattes, which I suspect may have been on location glass shots. The distant monastary on the peak was painted by veteran matte artist Joseph Natanson, who's career stretched way back to training under Percy Day's watchful eye through to a very busy and on demand role as freelance matte painter in Rome on a myriad of European productions. This was Joseph's final film. |

TRADITIONAL GLASS SHOTS IN THE DIGITAL ERA?

![]() |

| We may be in the digital era - like it or not - but this goes to prove that there's still some life left yet in those old oil paints and glass sheets. Here we see Leigh Took blocking in a glass shot for the wartime film THEIR FINEST HOUR AND A HALF (2015). |

![]() |

| A reverse angle of Leigh at work, which he told me was a refreshing change to get back to his roots. |

![]() |

| As an additional bonus, and probably a motion picture first, the matte artist gets to appear in the film himself at work on one of those very glass shots. |

![]() |

| Leigh Took - matte artist, actor and jack of all trades it would seem. |

![]() |

| I'm unsure of the context of all of this, but it's certainly an interesting first as far as I know. That's Leigh standing at the back by the light. |

That ought to do it for this mammoth blog post....."I've got blisters on 'me fingers.."

NZPete

In todays article I've assembled a mountain of, hopefully, illuminating material from a wide range of films that cover the whole gamut, from silent era trick shots, various travelling mattes and the variations therein, split screens, optical manipulations, twin effects and of course lots of great effects animation, all from a wide variety of films, some classics and some way at the other end of the spectrum. A number of frames have been collected from high resolution BluRay sourses so they look better than ever. So with that I hope you enjoy this selection.